Lesson 9a

Governance and democracy

How should a society be organised politically to approach sustainability? The basic document, which addresses this question, is the Agenda 21 from the 1992 Rio UNCED Conference. Here the importance of democracy with participation and involvement of all stakeholders in a society is underlined. Participatory democracy is thus seen as the political system under which it is possible to approach and govern a sustainable society. Democracy is also the system, which more than other systems guarantee the human values described in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. There are good reasons to choose democracy. Historical experience shows that strongly centralised authoritarian systems sooner or later disregard environmental protection, good resources management and human rights to protect its own power. Examples of such mismanagement are to be found both in history and in present regimes all around the world.

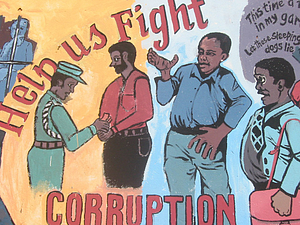

Democracy as a social invention has a long history but modern democracies did not exist until about 100 years ago. Since then, with setbacks under the first and second World Wars, as well as in connection with the decolonisation in the 1960s and early 70s, democracy has been introduced in a growing number of states. Today more than half of the world population live in formal democracies with universal suffrage. Difficulties when going from an authoritarian system to democracy includes that the citizens should take responsibility, even if there is no such tradition and many rather want a “strong leader” to take care of them. On the way to democracy to reduce corruption is typically a slow and difficult process, while free media is often in the forefront.

For sustainability democracy design is crucial. The traditional representative democracy, limited to voting, has not been able to respond to all demands of sustainable development. It lacked the elements of participation, listening, mutual understanding and changing views in the political process, which is present in participatory or, more often, deliberative democracy. This on the other hand characterises governance. Governance asks for less bureaucracy and an increased distribution of responsibilities of realisation, economy and maintenance in societal issues; it is more entrepreneurial, stresses competition, markets and customers, and measures outcomes. This transformation of the public sector, the authorities, may be summarised as less government but more governance.

The authorities build institutions for the purpose of implementing their policies. Some see institutional sustainability as the equally important as environmental, social and ecological sustainability. Institutions have the task of implementing, monitoring, reporting and regulating society according to the tasks given to them by the governing decision-makers. A task of special concern for sustainable development includes monitoring, e.g. emissions of greenhouse gases, presence of chemical pollutants, development in the field of energy etc. to give decision-makers the needed background; still this monitoring and reporting is much weaker than in e.g. the financial sector.

Democracies vary in distribution of power between the local and central levels. Sustainability politics typically stresses the role of the local level, and has Local Agenda 21 as the basic document. To be successful the local level needs three competences: legal, economic and expertise. The local level should thus have enough power to regulate on the local level, exemplified by the planning monopoly, enough economic strength to execute necessary reforms, which requires a strong local taxation, and finally the expertise needed to monitor and plan for a sustainable future. City networks such as the European Sustainable Cities and Towns Campaign asks for a strong local level development and the role of good governance, illustrated by the Aalborg commitments (See further Chapter 4a).

Democratic government and implementation of the principles of democracy has been monitored in various ways. A most interesting and relevant report is published by the World Justice Project, WJP, as an “effort to strengthen the rule of law for the development of communities of opportunity and equity”. The rule of law includes four principles: that government and its officials are accountable under the law; that the laws are clear, publicized, stable and fair; that the process by which the laws are enforced is accessible, fair and efficient; and that access to justice is provided by competent, independent, and ethical adjudicators.

The Word Justice Project index monitors the rule of law in nine segments: Limited government powers; Absence of corruption; Order and security; Fundamental rights; Open government; Effective regulatory enforcement; Access to civil justice; Effective criminal justice: and Informal justice. In 2011 a total of 66 countries had been assessed and reported for. Other important monitoring bodies include Transparency International, which measures corruption in the world since more than 20 years. Corruption is in many ways an equally serious threat to the development of a country as lack of democratic institutions or even climate change, as resources intended for development is used to build private fortunes.

The right to free exchange of ideas, to assemble and to organize is essential for the democratic process. Civil society refers to all individuals and organizations in a country that is not state or authority. Civil society organizations are referred to as Non-Governmental Organizations, NGOs. Many people see the topics of sustainable development, protection of nature, and the fight against climate change, as existential questions. Here the right to organize to influence political as well as other processes in society is essential. Such organizations play a very important role in the changes we see. The possibilities to influence have increased tremendously with the access to new information technologies.

Business, which may be included in civil society or seen as a separate sector, has a key role. In a modern, western state this the private sector accounts for some 85% of the economy. From companies and employees taxes are paid to the authorities on national, regional and local levels, to make it possible for them to execute the policies agreed on in the country. Since the 1970s Western Europe, and since 1990s Central and Eastern Europe, have undergone large-scale privatizations with enormous assets originally owned by the state transferred to the private sector, e.g. trains, mines, electricity, telephone and communications. More recently we also see social services become privatized, such as healthcare, schools, elderly care etc. This means that the attitudes and projects for sustainable development in the business sector are of key importance.

As a result national, regional and local authorities increasingly do not have enough political and financial power for planning and implementing plans. To plan for future changes and to be able to implement the plans, actors and stakeholders enter into different types of coalitions, public private partnerships (PPP). These include a mix of public and private actors, each capable of bargaining on their own behalf; partners are expected to bring something to the partnership, and share responsibility for the outcomes of their activities. Disadvantages include an unclear relation of responsibility between the population and their political representatives, and an increased risk of corruption.

Another key actor in the changes a society undergoes is science. Research at universities, academy institutions, and research institutes develop our knowledge and understanding of the world. Research financers, among them the state, largely select research priorities; during the last decade sustainability research have been well financed. The research results should be under constant discussion and criticism, and controversial results should at best provoke other scientists to try to replicate, falsify or confirm. This is part of a sound scientific process. But it appears that when science results are uncomfortable enough some politicians do not want to face the consequence, they rather attack the science on which they are built, which appears to explain some climate denial.

In a living democracy it is far from enough to express your view when voting each four or so years. Media like TV, radio, and newspapers, sometimes described as the third power in a state (the other being government and the court system) has a key role in a living democracy. It allows for an ongoing public debate, proposals and arguments, as well as distributing the result of science and research. In the best case the media serves to educate the population on a daily basis, which is a key question for sustainable development. Where democratic institutions are defeated media is usually the first victim, as power holders want to control all information distributed in the country, another illustration of the connection between democracy and sustainable development.

Materials for session 9a

Basic level

- Study Environmental Science, chapter 22 (pdf), especially pp 665-684: Making and Implementing Environmental Policy.

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 19 (pdf), pages 285-289: The Historical Breakthrough of Democracy.

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 21 (pdf), pages 296-299: Territorial Power Distribution.

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 22 (pdf), pages 300-307: The Civil Society: Parties and Associations.

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 25 (pdf), pages 333-343: Malfeasance in Contemporary Democratic Societies.

- An Agenda for Global Responsibility The Finnish Ministry of Education and the Baltic Univeristy Programme, 2008.

Medium level (widening)

- Study the World Justice Project in Constructing the WJP Rule of Law Index, p 7-17.

- What is Good Governance? By United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Pacific, ESCAP.

- Read on Non-governmental Organizations in Global Issues.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Study the role of Public-Private Partnership (PPP) in the Handbook of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) for their role in SD, e.g. infrastructure development.

- Study the role of NGOs in The Rise and Role of NGOs in Sustainable Development from International Institute for Sustainable Development, IISD.

Additional Material

Vladlena Gladchenko and Marie Thynell: The Political Dimensions of Sustainability .

References

Maciejewski, W. (ed.). 2002. The Baltic Sea Region – Cultures, Politics, Societies. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

Rydén, L., Migula, P. and M. Andersson (eds.). 2003. Environmental Science – understanding, protecting and managing the environment in the Baltic Sea region. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course