Lesson 3c

Measuring and managing resource flows

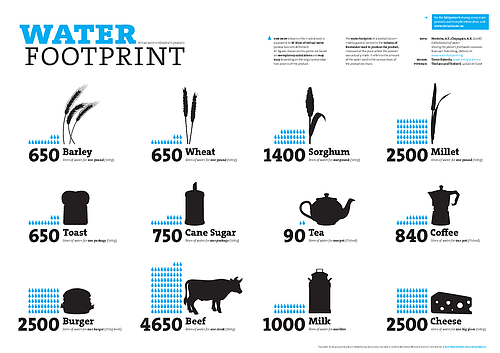

There are several ways to measure resource use. The best known may be the ecological footprint (See Session 3b) estimated in global hectares. Footprints may also be divided to show partial footprints. Carbon footprints specifically show carbon dioxide (or greenhouse gas) emissions, while water footprints specifically show water use for the product. Normally these footprints use a life cycle accounting and may come up with surprising results. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) normally has resource depletion as one input parameter, so very many LCA reports include resource use.

Total Material Flow is the most exact measure of resource flow and reflects impact best. The Total Material Requirements (TMR) of nations consists of the Domestic Material Input (DMI), which is the resources used in the countries’ economies, and the export. Within the European Union 15 it is about 40 tonnes per capita and year, a fairly constant figure despite increased GDP. Some countries are higher, such as Germany with 70 tonnes per capita and year, while e.g. Poland is lower, ca 30 tonnes per capita and year (2002 statistics).

40 tonnes per capita and year corresponds to a person coming home from weekly shopping with about 300 bags full of material. You may ask, “Where are these tonnes?”. They are imbedded in the products, as the so-called ecological rucksack of the products. A laptop typically weighs 1 tonne if its rucksack is included. The rucksack of a product can be calculated using the materials intensity factors for e.g. metals, agricultural products etc. These data are available at the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy, Germany, where also the rucksack (and MIPS) concept was developed.

The resource use may be calculated not only for products, but also for services. The measure used is called Material Intensity Per Service unit, MIPS. The MIPS depends on how a service is delivered. For example, if the service is transport from A to B, the MIPS will be very different for different modes of transport, such as car, bus, train, bike, or walking. The same is valid for the service of heating your flat or eating a lunch.

The Ecological rucksack and the MIPS include the life cycle of the product from resource extraction, energy use in the production etc. up to consumption. Further material consumption at the end of life of the product is not included, nor is the possible recycling. Still, the messages from the studies of material intensities are shocking. The leader of those studies, Friedrich Schmidt Bleek, therefore introduced the Factor 10 concept. It says that industrial nations need to reduce their material turnover by a factor of 10 (sometimes written Factor X) to reach sustainability. It accounts for that developing nations should be allowed to increase their resource use by a factor of 2 and the planet as a whole needed to reduce resource flow by a factor of 2.

The Factor 10 concept followed in the footsteps of the already established concept of Factor 4 – Doubling Wealth, Halving Resource Use. The Factor 4 concept was mostly asked for much improved resource efficiency in the word as a whole. The Factor 10 was more specific to the industrial societies and more difficult to accept. It is supported by UNEP, but not much used in the Baltic Sea region countries.

It is clear that we need to improve the resource flow on the Planet, in our societies and often in our personal lives. Resource flow management intends to limit and reduce the resource use for a product. The direct approach is to dematerialization a product, for example by making it smaller, or slowing down the flow by making it last longer, e.g. by making it easier to repair, by recycling the material and finally by substitution, using a different material which require less flow. There are a multitude of examples of how these principles have been applied.

There are many approaches to the dematerialization of our societies. Most importantly, we need to remember recycling. With closed material flows instead of linear (from extraction to landfill) we may reduce the material flows very much. We should also consider owning and using the products together. When we use a common printer instead of our private, it reduces the resource flows. The same is valid for using public transport instead of a private car, or joining a carpool.

When a product, service or – more broadly an economy – is delivered with much less resource use than earlier, it is called decoupling. One example is that western economies have grown for at least some 20 years without the same increase in resource use. But it seems that the extra resources becoming available due to decoupling is used for a new activity, which increases resource use. This is called the rebound effect. Due to the rebound effect, we get relative decoupling but not absolute decoupling, which is what we need.

So far, we have not seen a society where resource use decreases significantly. The Limits to Growth research team admit that some decrease can be made by technical developments (e.g. introducing solar electricity), but it is not enough. Changes in lifestyle are needed. A number of policy instruments need to be used to develop the societies in that direction.

Materials for session 3c

Basic level

- Read A Sustainable Baltic Region, session 3, pages 23-30: Towards Sustainable Materials Management.

- Calculate the MIPS for a Product The methods are illustrated by MIPS of a woman’s Polo-neck jumper in Product Design and Life Cycle Assessment, (pdf) pages 235-241.

Medium level (widening)

- Read Towards Sustainable Resource Management in the European Union by Stefan Bringezu, Wuppertal Institute.

- Read Factor 10: The Future of Stuff by Friedrich Schmidt Bleek.

- Read Chapter 2 Accounting for Material Flows and Chapter 3 Results, Implication and Conclusions in the Resource flows: the Material basis of Industrial Economies by World Resources Institute (pp 5-18).

- Get to know The Factor 10 Institute.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Study the 2009 monitoring report of the EU sustainable development strategy from Eurostat, Chapter 4 Sustainable Consumption and Production, pages 118-147, especially pages 124-128 (Domestic material consumption & Resource productivity).

- Read chapter 5, pages 49-59: The Myth of Decoupling in: Prosperity without Growth.

References

Adriaanse, A., Bringezu, S., Hammond, A., Moriguchi, Y., Rodenburg, E., Rogich, D. and H. Schütz 1997. Resource Flows: The Material Basis of Industrial Economies. World Resources Institute, Washington D.C.

Eurostat 2009. Sustainable Development in the European Union. Luxembourg.

Jackson, T. 2009. Prosperity without Growth – Economics for a Finite Planet. Earthscan Ltd, London, UK.

Karlsson, S. (ed.). 1997. Man and Materials Flows. A Sustainable Baltic Region. Session 3. Baltic University Press. Uppsala, Sweden.

Zbicinski, I. Stavenuiter, J. Kozlowska, B and H. van de Coevering. 2006. Product Design and Life Cycle Assessment. Book 3 in a series on Environmental Management. Baltic University Press, Uppsala, Sweden.