Lesson 12A

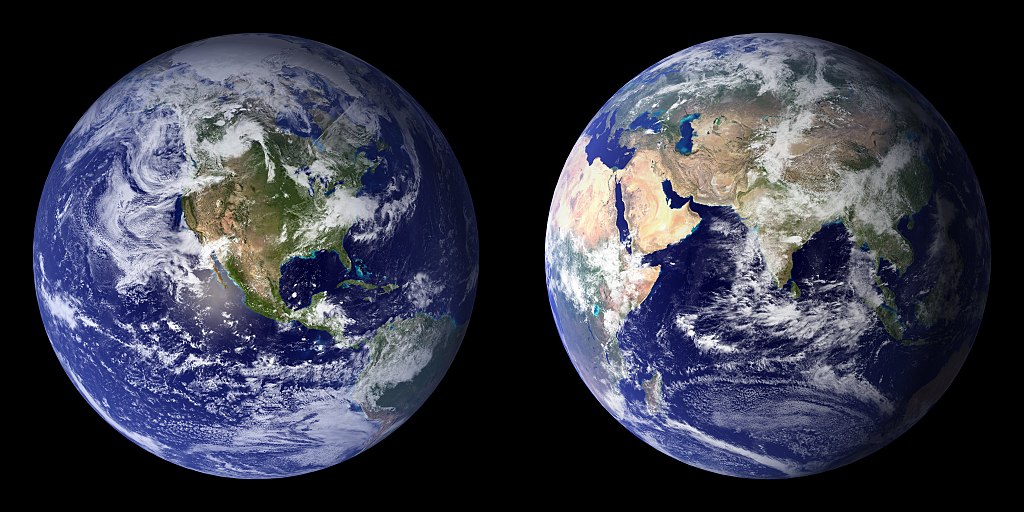

The politics of ESD

Education for Sustainable Development, ESD, has since the 1990s become a concept both in the world of education and the world of politics. Education has been recognized as the golden way to approach sustainability and is meant to be available to all parts of society and integrated in all kinds of schools. This session will look at ESD from all perspectives, the politics of education, as well as from the teachers’ and the learners’ side.

Environmental education was brought up as an essential component of environmental protection already at the 1972 Stockholm conference, and UNESCO was given the task to establish an international programme in environmental education. In 1975, UNESCO together with UNEP created the International Environmental Education Programme. Already here, the important components listed included interdisciplinarity, promotion of values and ethical responsibilities, commitments for actions and improvement of quality of life. All of these are today essential ingredients of ESD.

Two conferences/workshops dedicated to environmental education were arranged in Belgrade in Serbia in 1975 and in Tbilisi in Georgia in 1977. From the documents agreed on at these conferences, it is clear that the nature of environmental education is not similar to the ordinary subjects in schools or even in higher education. The systems understanding is emphasized: “to consider the environment in its totality, natural and man-made”; it is important that it is lifelong; it should deal with how to implement action and solve problems; the declarations of the conferences were accepted to a very different extent in different countries. In most cases, the ordinary curricula did not change much. In other countries, environmental education started as a component in biology. Here it was mostly education about (rather than for) the environment and had a considerable component of ecology.

In the meantime, a number of NGOs became very important actors in environmental education and their number of members increased. These groups were concerned about the state of the environment and acted to protect and conserve it. Some members of the environmental movement became extremely skilled, while others had a less scientific approach and were mostly concerned with a particular problem or site, which were threatened by pollution. NGOs in these years were – and still are – important political actors.

The 1992 Rio UNCED conference became a turning point in environmental education and changed it even formally into education for sustainable development. The Agenda 21 document mentions the word education several hundred times. Chapter 36 is entirely concerned with education. The basis for action for sustainable development should be increasing public awareness and public participation, which is entirely dependent on increasing substantially the general knowledge on environmental and sustainability issues in all layers of the population.

In the Baltic Sea region, the Agenda 21 document was developed into a regional action plan, the Baltic 21, in 1996. The original Baltic 21 had 9 sections, but none on education. After initiatives from several of the sectors, in particular the agricultural sector, Sweden together with Lithuania initiated a process, which led to the establishment of a special Baltic 21 sector for education finalized in 2002.

Still, the education sector was weak and further initiatives were taken to strengthen its agenda for ESD. The World Summit at Johannesburg in 2002 became such an opportunity. At this conference, research, education and business were in focus. On a Japanese initiative, the conference suggested that the United Nations should install a decade for education for sustainable development. Later in 2002 the General Assembly decided that a decade for ESD should be run during 2005-2014 under the leadership of UNESCO. This process, which is thus ongoing, had its midterm conference in Bonn in 2009. Presently, efforts are made to make ESD a permanent responsibility for UNESCO, thus continuing after 2014.

The national implementation of the decade has been very different. Since 2002 most countries have developed their national strategies for ESD. Some countries, including Sweden and Latvia, have passed laws, which make higher education institutions responsible for delivering ESD. The number of courses and master programmes in SD at universities in many countries are important. However, we have seen less of integrating ESD in other subjects.

UNECE (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, the USA, and Canada) have been very active to promote ESD. Already, the conference of ministers of environment in Kiev in 2003 drew up preliminary lines for an UNECE strategy for ESD. The strategy was developed and accepted at a conference for ministers of environment and education in Vilnius in 2005, thus marking the start of the Decade. The strategy has since been revised, and the most recent version was published in 2011.

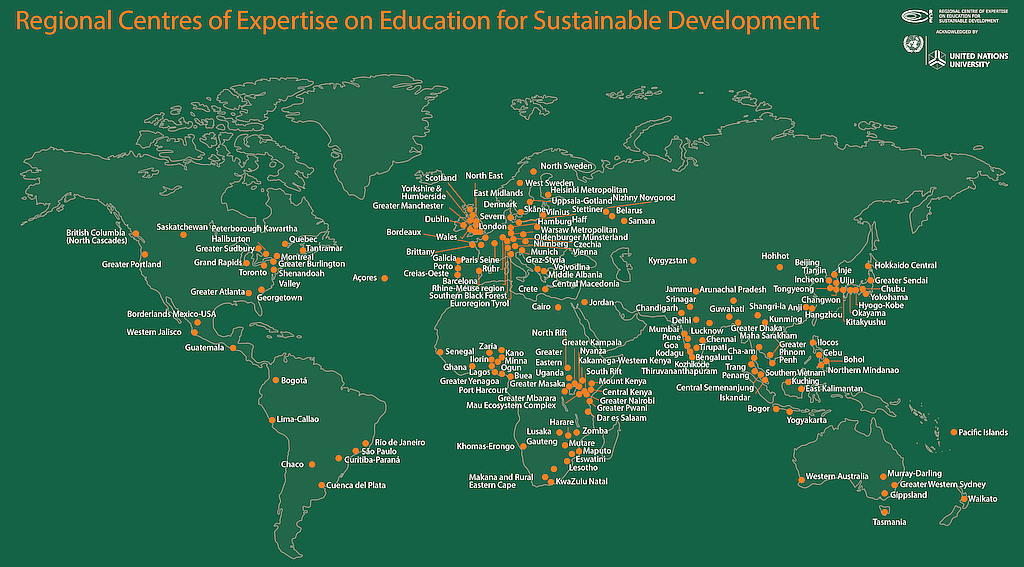

Several initiatives to strengthen and develop networks for education for sustainable development have been taken both in NGOs, in schools and universities. In the Baltic Sea region the Baltic Sea Project, BSP, is a cooperation between schools in 9 countries with hundreds of participating schools. Among universities the Baltic University Programme, BUP, is the largest network in higher education for ESD, but we also see networks of universities for ESD in the Mediterranean. On a global scale, the Life Link network for schools has a large component of ESD. The UN University in Tokyo has instantiated the establishment of Regional Centres of Expertise, RCEs, now developing in many parts of the world. These are coordinating bodies between cities, schools universities and companies in a region, or even a country, promoting ESD. There are today some 100 RCEs; good cases are found, e.g. in the Netherlands.

Materials for session 12a

Basic level

- Study the development of environmental education in the Environmental Science, chapter 21 (pdf), especially pages 645-651: Behaviour and the Environment – Ethics, Education, and Lifestyle.

- The UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005-2014) by UNESCO is introduced here.

- The UNESCO site for Education for Sustainable Development is a very rich resource on all aspects of ESD and how it is understood and implemented today.

Medium level (widening)

- Agenda 21, Chapter 36: Education, Training and Public Awareness

- Regional Centers of Expertise (RCE) of United Nations University includes basic description and links to new and all individual RCEs.

Advanced level (deepening)

Study some of the networks for ESD:

- Baltic University Programme

- Baltic Sea Project

- Life-link

- Baltic 21 and The Haga Declaration

References

Rydén, L., Migula, P. and M. Andersson (eds). 2003. Environmental Science – understanding, protecting and managing the environment in the Baltic Sea region. Baltic University Press. Uppsala, Sweden.