Välkommen till Svenska Aralsjösällskapet

7a.

A culture of mobility

Mobility is a main aspect of life. Many species travel extensive distances as parts of their annual or even daily life patters. We may remind ourselves of migratory birds, of herding animals moving for grazing land or carnivores roaming vast territories. Man seems to be such a mobile species. Just walking around is for many a pleasure in itself. More extensive travels such as hiking in the mountains, pilgrimages or “wanderings”, are for many a pleasure and enjoyment, for some the best in life.

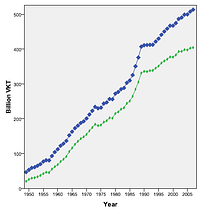

Yet in our societies 100 years ago almost everyone was stationary. The dialects remind us of that. On the average, a person in Sweden (probably the same in most countries in the region) moved not further away than 1 km a normal day, typically by foot.  Today this figure, the extent of mobility, is closer to 35 km per day and almost twice as high for those – especially middle-aged men – with the highest mobility. On average, we travel close to one hour per day. It appears that this time is fairly constant over time, but the distance covered increases with faster cars, buses, trains, flights and better roads. Mobility has been increasing faster than GDP in many countries, and it is still increasing in e.g. the three Baltic States and Poland. When we have more money, we use much of it for travel.

Today this figure, the extent of mobility, is closer to 35 km per day and almost twice as high for those – especially middle-aged men – with the highest mobility. On average, we travel close to one hour per day. It appears that this time is fairly constant over time, but the distance covered increases with faster cars, buses, trains, flights and better roads. Mobility has been increasing faster than GDP in many countries, and it is still increasing in e.g. the three Baltic States and Poland. When we have more money, we use much of it for travel.

There are many advantages of mobility. Better possibilities to travel means that an individual may more easily meet friends and family, take an attractive job further away, and visit distant shops, and sport events. These possibilities are highly valued by many and increase our quality of life and freedom. To be able to travel, to visit interesting places, enjoy sun and beaches and relax is a most favoured possibility in the welfare states where many have economic means and are healthy. In Sweden some 350,000 individuals travel to Thailand for holiday each year, to be compared to one or two generations ago when the typical destination was somewhere in Sweden, followed by the Mediterranean one generation ago.

Mobility is of two kinds. So-called forced mobility is travelling which is not wanted by the individual, but required for work and needed social services. Most typical, this includes commuting between home and work. Travelling as part of the job is also increasing rapidly. Voluntary mobility is travel chosen by the individual, for example in connection with free time and tourism. Voluntary mobility, especially for tourism, is an important part of most peoples’ lives.

Tourism is one of the most rapidly increasing sectors of our economy. Tourism requires travel. So-called sustainable tourism seems not to include travels in their concept, as it is dealing mostly or only with what is happening at the tourist site. Most people select the cheapest way to travel, which for longer distances almost always is by air. Air travel increases very rapidly. It is also the most polluting in terms of emissions of carbon dioxide and other GHGs per person kilometre. We see a small increase in long distance train travel, which has much fewer emissions. How to make tourism more sustainable is a very difficult challenge.

Mobility may mean different things, from walking, travelling by bike, rail, boat and air, but today mobility is completely dominated by car use. Within the European Union (EU 27) about 85% of all kilometres travelled are by car. In interviews, most people refer to comfort and speed as the reason for using a car. It is interesting that those preferring other modes of transports from bikes to trains also refer to comfort and speed when asking why they prefer this mode of transport. But car ownership certainly has more dimensions than practical for transport. For many, a car symbolizes freedom, independence, and status.

Car ownership increases in society, with economy up to much more than one car per household. Cars are many, and it shows in the larger cities as congestion up to the point when car use becomes difficult, and restrictions have to be introduced by authorities. Some cities (e.g. Stockholm, Oslo, and London) restrict car use by a tax on entering the city. If all German cars were on the roads simultaneously, the average distance between them would be 12 meters. Cars are also a major factor on the economy of our societies. If sales, repair, fuels, insurance etc are all included it totals some 10-15% of the economy of Western Europe and a large share of all work opportunities.

The increased preference for cars has obvious consequences for how our cities, villages, and countryside looks like. The mobility infrastructure is a key feature of our societies. Traffic-scapes are dominating our outdoor environment, especially in cities but also in countryside. In cities this is mostly negative for culture and the architecture, possibilities to meet and social relations. In cars, people are isolated and do not interact. “Reclaim the cities” is a counterforce; the increased number of car-free city centres as well. In the countryside, roads and railroads are cutting off mobility for animals, and reduce biodiversity. It is sometimes attuned by animal tunnels and bridges.

The high level of mobility has large costs and is at present not sustainable. The three most serious consequences are environmental impacts, energy use and a high level of accidents. Each of these is multifaceted, serious, and difficult to reduce. Today, these costs have increased far beyond what is sustainable. Instead, it appears that mobility and travel is one of the largest, perhaps the largest, challenge in the transition to a sustainable society.

Car traffic is mainly responsible for these effects. It is a large consumer of oil. The transport sector accounts for about 40% of GHG emissions in Western Europe, a share which is increasing. Ways to make transport less dependent or even independent on fossil fuels are thus necessary. Pollution of air by car exhausts is also serious and causes large negative health effects. The rate of accidents in the transport sector is serious. In the EU25, 44,000 fatalities occurred in road traffic in 2004, and very many more were seriously injured.

Car traffic is mainly responsible for these effects. It is a large consumer of oil. The transport sector accounts for about 40% of GHG emissions in Western Europe, a share which is increasing. Ways to make transport less dependent or even independent on fossil fuels are thus necessary. Pollution of air by car exhausts is also serious and causes large negative health effects. The rate of accidents in the transport sector is serious. In the EU25, 44,000 fatalities occurred in road traffic in 2004, and very many more were seriously injured.

But there are other ways to move than by car. Biking has many advantages over car traffic, but of course do not compete at longer distances. Public transport, when functioning properly, is as well a more sustainable alternative. Choosing these means of transport over car is very much a question of mobility lifestyle. In larger cities in the world it appears that there is a new trend as car ownership is decreasing slowly since a few years.

Materials for session 7a

Basic level

- Read A Sustainable Baltic Region, session 6, chapter 1: The Challenges of Mobility.

- Read A Sustainable Baltic Region, session 6, chapter 2: How and Why – The Development of Mobility.

- Read A Sustainable Baltic Region, session 6, chapter 3: The Cost of Transportation – Energy and Environmental Impact.

- Steps to Improve Sustainable Mobility (at youris.com).

Medium level (widening)

- Exploring Mobility Solutions — Civitas. The Civitas EU project is a resource for a long series of EU projects for Sustainable mobility.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Read A Sustainable Baltic Region, session 6, chapter 5: Approaches to Sustainable Mobility.

- Read A Sustainable Baltic Region, session 6, chapter 8: Life-Style and Mobility.

- Read the Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030 (UN United Nations Road Safety Collaboration and other stakeholders).

References

Tengström, E. and M. Thynell. (eds.) 1997. Towards Sustainable Mobility – Transporting people and goods in the Baltic Region. A Sustainable Baltic Region. Session 6. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

7b.

Means of mobility – technology and systems

Since the environmental impacts of transport are so large, the means we use to transport ourselves or our goods are of key importance. There has also been a considerable development of the technology of transport. Equally important is the development of transport infrastructure as well as the organization of transport and its alternatives from walking, biking, cars, public transport to information technologies. Many approaches to sustainable mobility rely on technical developments, such as green cars, or organizational developments, such as design of urban transport. These issues will be addressed in this subsection.

As car travel is so dominating in our present system, the development of the car is crucial. There are some fundamental shortcomings of the present conventional car. It depends on fossil oil; it is comparatively heavy, often close to one tonne; the air pollution caused by cars is serious; cars are noisy especially at higher speeds and take much space in cities, etc. Environmentally better alternatives to the conventional car are those using less fuel, either because of being diesel, or smaller, and those using alternative fuels, such a bioethanol or biogas.

In a conventional car, the combustion motor is very inefficient. Typically, some 18% (petrol) or 22% (diesel) of the energy in the fuel is used to move the wheels. The rest becomes heat. In an electric car this efficiency is much higher, at best case closer to 80-90%, which is, about four times as much as the combustion engine. That is why in a sustainable transport system, electric cars are expected to be an important component. The largest difficulty today is the means to store electricity, the batteries. The best cars today allow about 150 km until batteries need recharging. This is not necessarily a serious shortcoming, since the large majority of car travels are much shorter. Recharge of electric cars may be done at home, for plug-in cars, at charging stations or by fast exchange of batteries. There are also hybrid cars (electric and combustion), using electric the motor for the many small trips and the conventional for longer ones. A sustainable electric car requires of course that the electricity used is renewable.

In a conventional car, the combustion motor is very inefficient. Typically, some 18% (petrol) or 22% (diesel) of the energy in the fuel is used to move the wheels. The rest becomes heat. In an electric car this efficiency is much higher, at best case closer to 80-90%, which is, about four times as much as the combustion engine. That is why in a sustainable transport system, electric cars are expected to be an important component. The largest difficulty today is the means to store electricity, the batteries. The best cars today allow about 150 km until batteries need recharging. This is not necessarily a serious shortcoming, since the large majority of car travels are much shorter. Recharge of electric cars may be done at home, for plug-in cars, at charging stations or by fast exchange of batteries. There are also hybrid cars (electric and combustion), using electric the motor for the many small trips and the conventional for longer ones. A sustainable electric car requires of course that the electricity used is renewable.

Also, the combustion motor car has been made more sustainable by using renewable fuels. The biofuels include biogas, bioethanol, and biodiesel. In some situations, the use of biofuels may be the best alternative. When food waste and other organic waste in a city are used for biogas production, it may be sufficient for all city buses, thus establishing a sustainable recycling system. Large-scale production of bioethanol is only sustainable if it is not using fossil fuels during production, or it is competing with other more important uses of the crop. Bioethanol is today the dominant biofuel but is not considered to be a long-term solution. Similar considerations are valid for bio diesel. Both are today mixed in standard fossil fuels to decrease CO2 emissions from traffic.

A large part of the energy consumption in cars is caused by friction between the tyres and the road. That is why rail traffic is energy-wise so much better than road traffic. Electric vehicles on rail, trains and trams, are the most energy-efficient way to move both people and goods on land. A well functioning metro, tram, and local train systems are important components of a sustainable transport system in a city. Train traffic is also the best alternative for freight traffic on land. Fast trains have the possibility to replace much air travel without much time loss and much comfortably running from city centre to city centre, with dramatically reduced environmental impact.

Air traffic only accounts for only about 1% of total travel, but still about 800 million passengers were carried by air in 2010 in the EU-27. Air traffic has the largest environmental impact per person kilometre. There are small possibilities to reform air traffic into a more sustainable system, although research is ongoing to produce biofuel for aeroplanes from wood. The most reasonable development now is to substitute shorter air travels by fast trains, and use more ICT for business meetings.

Boat traffic is expanding fast, both for business and pleasure. Environmental impacts from boat traffic include emissions of carbon dioxide and acidic SOx, especially from the use of oil with high sulphur content. There are also many cases of toilet and other organic waste emitted right into the sea. Regulations to reduce environmental impacts of boat traffic are much needed, but only slowly implemented.

Obviously, transport would be more efficient if more people would share the same vehicle. This is done in public transport. Here the emissions per person kilometre is drastically reduced both when bus is used, and even more so in train or tram. Traffic infrastructure would be much better with more public and less private transport, and congestion would diminish. Research suggests that most important for good public transport is to avoid waiting and time lags.

Obviously, transport would be more efficient if more people would share the same vehicle. This is done in public transport. Here the emissions per person kilometre is drastically reduced both when bus is used, and even more so in train or tram. Traffic infrastructure would be much better with more public and less private transport, and congestion would diminish. Research suggests that most important for good public transport is to avoid waiting and time lags.

Halfway between private and public transport is car sharing, that is, when a group of people, e.g. living in the same neighbourhood, have a number of cars together, a so-called carpool. Car sharing has many advantages. The cars are used more when compared to private car, the maintenance of the cars may be organized in a way so that each user is not concerned. If car sharing is a good alternative depends on the situation for the individual, but car sharing is increasing in big cities, and the number of cars in big cities are decreasing in many countries.

Biking has many advantages as means of transport. There are no emissions, the infrastructure needed for biking (bike paths and parking) is small, the costs are small compared to cars, it is healthy for the individual, and many bikers like to be “outside”, rather than inside a car or bus. Most bikers do not travel long distances. Mean speed of biking is about 20 km; in 20 minutes you travel some 6 km. Biking in cities are on the increase, also in large cities, e.g. Paris and London, and in others, e.g. Copenhagen and Amsterdam, it is established since long. In Stockholm, 150,000 commute daily to the workplace by bike, a figure expected to double in ten years. There is a huge untapped potential for biking in cities in Central and Eastern Europe.

Biking has many advantages as means of transport. There are no emissions, the infrastructure needed for biking (bike paths and parking) is small, the costs are small compared to cars, it is healthy for the individual, and many bikers like to be “outside”, rather than inside a car or bus. Most bikers do not travel long distances. Mean speed of biking is about 20 km; in 20 minutes you travel some 6 km. Biking in cities are on the increase, also in large cities, e.g. Paris and London, and in others, e.g. Copenhagen and Amsterdam, it is established since long. In Stockholm, 150,000 commute daily to the workplace by bike, a figure expected to double in ten years. There is a huge untapped potential for biking in cities in Central and Eastern Europe.

Walking is of course positive both for health and environment. The recommendation is that each one of us need to take about 10,000 – 12,000 steps daily to keep healthy. This corresponds to about one hour of walking a day, which will take you about 6 km.

Walking is of course positive both for health and environment. The recommendation is that each one of us need to take about 10,000 – 12,000 steps daily to keep healthy. This corresponds to about one hour of walking a day, which will take you about 6 km.

Urban planning based on car use does not promote sustainability. Shopping malls designed after American models assume that almost all customers use his/her own car. A consequence is that small shops in the city centre have difficulties to attract customers and may be forced to close. This makes the city centre less alive and interesting. Small shops have higher prices, but then the costs of car use are not included in the comparison. In city centres, car free areas are increasing, which is not negative for shop owners.

The most sustainable alternative for mobility is not to move at all. This has become a realistic alternative with the development of information and communication technologies, ICT. Many business meetings can now be made using video conferencing via the Internet rather than travelling. This was illustrated in the months after the September 11 when air travel decreased drastically and many business trips were substituted for by ICT. Even if a small share of trips are substituted for by ICT, it would be important, especially for those where long distance travel is needed. A related phenomenon is “working home” strategies using computer and phone. Many office workers work in home one day in a week, which reduced commuting by 20%, which is significant. Savings when reducing travel is triple: time, costs and emissions.

Materials for session 7b

Basic level

- Read A Sustainable Baltic Region, session 6, chapter 6: Technical Solutions – Improved Transport Technologies.

- Read A Sustainable Baltic Region, session 6, chapter 4: Poland – The Private Car and Public Transport in Conflict.

Medium level (widening)

- Read A Sustainable Future for Transport: Towards an integrated, technology-led and user-friendly system (EU Commission report)

- International Association of Public Transport, UITP

Advanced level (deepening)

- How Electric Cars Work in Howstuffworks by Marshall Brain

- The UITP Sustainable Development

References

Tengström, E. and M. Thynell. (eds.) 1997. Towards Sustainable Mobility – Transporting people and goods in the Baltic Region. A Sustainable Baltic Region. Session 6. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

7c.

Freight

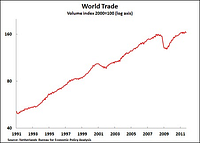

Freight is the transport of goods from one site to another. International freight is part of trading and, national freight of business operations. Freight and international trade has been part of our societies since our deepest history. In the Baltic Sea region, we had the Hansa as a medieval trading network. Today it is the European Union in which free trade is part of the four freedoms – free mobility of people, goods, services, and money – as its fundamental goals. Trading increases since several years, with about 6% annually in the Union. With globalization, transport routes are also increasingly global: We eat bananas from Guatemala, lamb from New Zealand, drive in Japanese cars, and our toys are made in China.

Freight is the transport of goods from one site to another. International freight is part of trading and, national freight of business operations. Freight and international trade has been part of our societies since our deepest history. In the Baltic Sea region, we had the Hansa as a medieval trading network. Today it is the European Union in which free trade is part of the four freedoms – free mobility of people, goods, services, and money – as its fundamental goals. Trading increases since several years, with about 6% annually in the Union. With globalization, transport routes are also increasingly global: We eat bananas from Guatemala, lamb from New Zealand, drive in Japanese cars, and our toys are made in China.

The original reason for trade was to distribute goods from one place to another, where it did not exist. Today this is still valid, but much more important is that business reduces costs by allocating the manufacturing of goods or other kinds of production to places where it is most advantageous, mostly because of cheaper labour. As the cost of freight in general is low – on average about 6% of the price of a product is due to transport – this relation is expected to continue, at least until the cost of transport increases. Today, road transport in the EU is increasing faster than GDP.

Transport and freight have costs, many of them not included in the price. They mostly depend on the use of fossil fuels in cars, trains, ships, and aircraft. To this is added air pollution, especially from ship transport, which too often uses dirty oil, but also by cars. Freight traffic is dominating our traffic infrastructure and requires even more expansion of roads. Trucks cause road accidents, congestion, and ships cause oil spills. The costs of these are mostly external, that are not included, in the price of the products. Environmental costs of transport were estimated to be 500 billion Euros for 19 member states in year 2000. Emissions of CO2 caused by road transport increased 17% between 1995 and 2005. In Western Europe, 73% of total land freight transport was on road in 2005.

Which are the possibilities to increase the sustainability of the freight sector? Obviously, it cannot continue to grow forever. Probably this requires that the costs for services have to be more equal in different parts of the world. Consumer pressure to buy items, which are locally produced, is another factor most important for food. The solutions are much seen as technical rather than decreasing transport. Increase of train use, use of electric powered trucks, e.g. by having electric cables along main routes is a much discussed option, as is improved organization.

The freight sector itself may also organize itself in ways that drastically reduces emissions and pollution. Thus, moving transport from roads to railroads is an important step, especially if the trains use renewable electricity. A way to do this is to use so-called intermodal transport. This means that goods may use several modes of transport – road, rail or ship – during its journey. The standard container allows goods to be packed in containers, which may be moved from car to rail to boat to car. The shift from one mode to another occurs at intermodal junctions. To make intermodal transport a future standard for goods handling is now EU policy.

The freight sector itself may also organize itself in ways that drastically reduces emissions and pollution. Thus, moving transport from roads to railroads is an important step, especially if the trains use renewable electricity. A way to do this is to use so-called intermodal transport. This means that goods may use several modes of transport – road, rail or ship – during its journey. The standard container allows goods to be packed in containers, which may be moved from car to rail to boat to car. The shift from one mode to another occurs at intermodal junctions. To make intermodal transport a future standard for goods handling is now EU policy.

Materials for session 7c

Basic level

- Read A Sustainable Baltic Region, session 6, chapter 9: Freight Transport – How to Make it Sustainable.

- Read Roadmap to a Single European Transport Area — Towards a competitive and resource-efficient transport system (EU Commission report)

Medium level (widening)

- Read A Sustainable Future for Transport: Towards an integrated, technology-led and user-friendly system (EU Commission report)

- Greening Transport Package – Frequently asked questions

- Read 12 Trends That Will Drive the Future of Transport

Advanced level (deepening)

References

European Commission. 2009. A sustainable future for transport — Towards an integrated, technology-led and user-friendly system. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Tengström, E. and M. Thynell. (eds.) 1997. Towards Sustainable Mobility – Transporting people and goods in the Baltic Region. A Sustainable Baltic Region. Session 6. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

7d.

Policies and management of mobility

Mobility and transport are central in our societies and have large benefits but, at the same time, high environmental costs. To reduce these costs, without causing too great problems for large groups in our societies, is difficult. Nevertheless, it is necessary if we should approach a sustainable society. Some necessary measures seem fairly clear, as transport research points out. The combustion car has to be largely exchanged for the electric car. This will take time. The limited and expensive battery is the largest obstacle. We will also have to drive car less, especially in cities; an estimation for Stockholm is 15-30% less. This corresponds to car driving on 1985 level. It is not difficult to live in a city without a car when public transport and biking is working well. In Stockholm, half of the households do not have a car today. Transport has to move to train and boat, while sustainable air traffic is so far an unsolved dilemma.

National transport polices exist in all countries, and also on the European level. Policies for transport may also have been taken in regional and local authorities, as well as by companies or organizations. These are however dependent on the actions taken on the national level, as the regulations and taxation belong to this level. The dilemma for policy actions is to balance the needs of transportation against the costs. An important part of the policies is to make more sustainable alternatives more attractive and the less sustainable alternatives less so. This may be done by supporting the more sustainable alternatives. On the national level, it is for example possible to invest in the development of train traffic or fast trains.

On the local and regional level, it is possible to support sustainable transport by good urban planning. The goal is to make a pleasant living environment and avoid traffic congestion, and decrease air pollution, noise and accidents. Investments in and development of public transport is important. Curitiba in Brazil became a symbol for good design of urban planning and public transport based on a clever fast-bus system. A culture and support of biking is efficient, illustrated by Amsterdam in the Netherlands. Car-free city centres or other car-free areas increase. A fee for entering the city centre by car has been introduced in e.g. London, Oslo, and Stockholm. Copenhagen has made car parking difficult and expensive. The introduction of such measures requires that local public transport works well.

On the local and regional level, it is possible to support sustainable transport by good urban planning. The goal is to make a pleasant living environment and avoid traffic congestion, and decrease air pollution, noise and accidents. Investments in and development of public transport is important. Curitiba in Brazil became a symbol for good design of urban planning and public transport based on a clever fast-bus system. A culture and support of biking is efficient, illustrated by Amsterdam in the Netherlands. Car-free city centres or other car-free areas increase. A fee for entering the city centre by car has been introduced in e.g. London, Oslo, and Stockholm. Copenhagen has made car parking difficult and expensive. The introduction of such measures requires that local public transport works well.

Taxation of car driving is an important measure to reduce car traffic. The several taxes and charges used include tax when buying a car, tax for mileage, insurance costs and inspection costs. Most important is tax on fuel and carbon dioxide emissions. If tax on petrol is high, fuel-efficient cars will be more attractive. Taxation may be differential. Carbon dioxide taxation does not apply to renewable fuels, such as biogas, bioethanol or biodiesel, which increase the market for cars using such fuels. So-called green cars, mostly cars using renewable fuels, may be exempt from some taxation, such as entrance fees to city centres.

Taxation of car driving is an important measure to reduce car traffic. The several taxes and charges used include tax when buying a car, tax for mileage, insurance costs and inspection costs. Most important is tax on fuel and carbon dioxide emissions. If tax on petrol is high, fuel-efficient cars will be more attractive. Taxation may be differential. Carbon dioxide taxation does not apply to renewable fuels, such as biogas, bioethanol or biodiesel, which increase the market for cars using such fuels. So-called green cars, mostly cars using renewable fuels, may be exempt from some taxation, such as entrance fees to city centres.

There are also regulations on cars and other forms of transportation. This includes safety measures such as speed limits, which also reduced emissions, which increase steeply with high speed. Within the EU, there is a maximum allowed level of carbon dioxide exhausts per kilometre of driving, at present 125 g/km. This figure will be reduced with time.

Mobility management is a management approach to making transport more sustainable. Mobility management is most often local and is centred at an information office in a city. The managers help individuals and also groups to find the best and the cheapest alternatives, e.g. for commuting. A Mobility Management Centre typically also runs projects. Here are some examples: organizing a biking schools for kids; negotiating an agreement between employed at a big hospital with the bus company for low price tickets; Restoration of an old railway to an industrial plant to avoid truck traffic in a city; Coordinating all transports to shops in city centre from a logistics central in the outskirts the city. Many Centres in the EU have joined the European Platform on Mobility Management, a European resource for Mobility Management.

Materials for session 7d

Basic level

- Read A Sustainable Baltic Region, session 6, chapter 7: Economic Policy Instruments.

- Read Environmental Management, book 1, chapter 10: Economic Policy Instruments — Taxes and Fees, especially Section 10.3 Environmental Taxes on pages 140-146.

- Read Bringing Quality to Life – The contribution of the public transport sector to sustainable development (more management).

Medium level (widening)

- Read A sustainable future for transport : Towards an integrated, technology-led and user-friendly system (EU Commission report)

- EPOMM is the European Platform on Mobility Management

- Read about the European Mobility Week campaign

Advanced level (deepening)

- Study a national l transport policy. This is for Ireland: A Sustainable Transport Future – A New Transport Policy for Ireland 2009-2020

- Policy Scenarios for Sustainable Mobility in Europe – the POSSUM Project

- Study how to organize a mobility management centres in the Mobility Management User Manual. Look for a centre in your own country.

References

European Commission. 2009. A sustainable future for transport — Towards an integrated, technology-led and user-friendly system. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Klemmensen, B., Pedersen, S., Dirckinck-Holmfeld, K.R., Marklund, A. and L. Rydén. 2007. Environmental Policy – Legal and Economic Instruments. Environmental Management Book 1, Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

Tengström, E. and M. Thynell. (eds.) 1997. Towards Sustainable Mobility – Transporting people and goods in the Baltic Region. A Sustainable Baltic Region. Session 6. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

8a.

Demography and population change

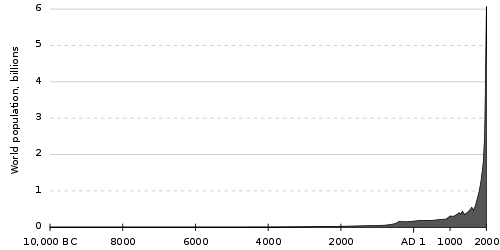

Fear for unending population growth – the population explosion – has since long been a main concern for those thinking about the future of humanity. The Englishman Thomas Malthus in An Essay on the Principle of Population from 1798 alarmed the world that food and other resources soon would not be enough for everyone and started a serious discussion on which political actions were needed to curb population growth. Today this discussion seem to be most active in the United States, where environmental impact is much perceived as the result of being too many, not that each one uses too many resources.

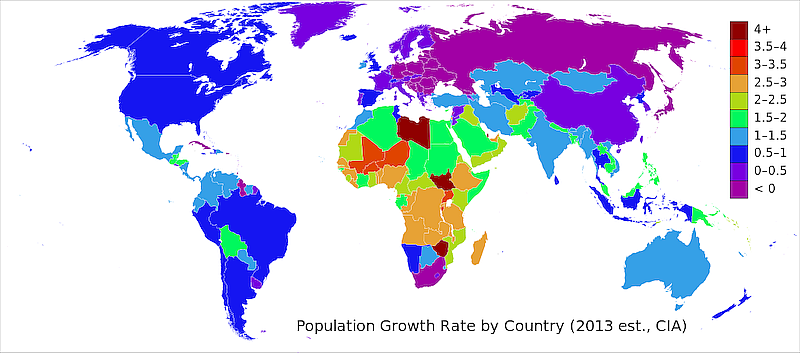

During most of human history, world population grew very slowly. On average a woman during her short life got 6 children of whom 2 survived to adulthood. This has changed as healthcare and food supply has improved. From the 18th century global population growth accelerated, with shortening doubling times, 1 billion in 1800, 2 billion in 1927, 4 billion in 1974 and 7 billion in 2011. However, since the early 1990s the rate of increase is diminishing and growth is expected to end by about 2050 at a world population of about 9 billion

Will the resources of the world be sufficient for 9 or so billion inhabitants? Is the carrying capacity enough? Most researchers believe that enough food for all will be possible. One will however have to decrease food loss, and improve agricultural productivity in many areas, not the least in Africa. However, we see land prices increase steeply in many parts of the world as an indication that the food production issue is expected to be critical.

In individual parts of the world, this development from a small population to exponential growth to finally levelling off at a higher level has already taken place. It is called the population transition. It begins when health improves, life expectancy increases and birth rate dramatically decreases. After some time, family size will shrink. An important reason for this is decreasing child mortality. It will thus not be necessary to have many children to be taken care of at an older age; as children go to school, they are also more a cost than a help in the household; and finally that families choose to have fewer children for improving their own lives. Of course, basic family planning has to be available to make these changes possible. These insights also point to what is needed to curb population growth.

A generation or two ago the so-called developing countries had many children per woman often about 6, and a population growth approaching 3%, while in developed, industrialized countries the figure was closer to 2.1 children, which is the replacement rate. Since then, a dramatic change has taken place. Especially in Asia, birth rates of many countries have dramatically decreased. High birth rates today only remain in Africa. In all of Europe the birth rates are lower than replacement rates and in some countries much lower, e.g. in Southern Europe. In Central and Eastern Europe, population decline is typical, both because of low birth rates and emigration.

An effect of improved health status of the population is that life expectancy is increasing. Life expectancy at birth globally was 68.3 years in 2010, but there are large regional differences. Highest is Japan with 82.6 years, while in many African countries the value is around 40 years. In Sweden in 2011 life expectancy at birth was 83.7 for women and 79.8 for men. Life expectancy is increasing with about 3 months per year in Europe, mostly because mortality at higher age is decreasing. If this development continues, living to 100 years of age will be common in the near future.

An effect of improved health status of the population is that life expectancy is increasing. Life expectancy at birth globally was 68.3 years in 2010, but there are large regional differences. Highest is Japan with 82.6 years, while in many African countries the value is around 40 years. In Sweden in 2011 life expectancy at birth was 83.7 for women and 79.8 for men. Life expectancy is increasing with about 3 months per year in Europe, mostly because mortality at higher age is decreasing. If this development continues, living to 100 years of age will be common in the near future.

As a sustainable society in the long term cannot have a steadily increasing population, we will have an ageing society. A much larger share of the population will be retired, and a common heard concern is that fewer (in working age) will have to support many more (retired). Another concern is that costs for elderly care will increase dramatically. Very few countries have developed a policy to manage this question. Rather, many countries try to decrease average age by stimulating families to have more children or immigration. However, this is only to postpone the problem, which will reappear but at a much higher total population.

When state guaranteed pensions were introduced the retirement age was equal to average life expectancy, that is, pensions were not a large cost for the country. Today, the pension age is debated. We see proposals to increase the age of retirement coupled with efforts to encourage elderly to stay at their working places voluntarily, often on part-time and with less heavy jobs. But there may also be voluntary contributions in many sectors of society by elderly who has a considerable experience in helping young people. Examples include business angels, elderly business leaders helping younger to get started. We have also seen healthy elderly taking care of less healthy elderly. It should in addition be said that according to macroeconomic modelling the average working hours in a sustainable economy should decrease substantially compared to the norm today, the 40-hour week. In a more sustainable society, it may be enough that a smaller section of society is working.

Materials for session 8a

Basic level

- Watch Hans Rosling on Global Population Growth (YouTube film).

- Watch Hans Rosling: New Insights on Poverty and Life Around the World (YouTube film).

- Read EHSA, book 3, chapter 8: Demographic Development in the Baltic Sea Region.

- The Demographic Transition by Keith Montgomery, University of Wisconsin.

Medium level (widening)

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 39, pages 495-509: Populations Around the Baltic Sea.

- Ageing of Population by Leonid A. Gavrilov and Patrick Heuveline.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Examine how your country is preparing for an ageing society. As examples, two documents are given:

For Sweden from the Swedish Institute.

For Poland from Ewa Fratczak Warsaw School of Economics.

References

Maciejewski, W. (ed.) 2002. The Baltic Sea Region – Cultures, Politics, Societies. Uppsala. Baltic University Press.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

Sida 9 av 15