10b.

The dilemma of economic growth

We live in a society in which economic growth has become a mantra for all policymakers and business people. Even if the overwhelming focus on growth is only some 30 years, the history of economic growth is long. Only during the 20th century, global GNP increased 16 times, see Chapter 1a. Among the several factors behind growth, energy stands out as the most important. The access to cheap fossil fuel is closely linked to economic growth during over a long period. Easy access to energy made labour productivity rise by some 3-4 % yearly over more than a century. A person equipped with a machine can do much more than when just using muscle power!

But where does a never ending economic growth take us? Suppose that all inhabitants should have the standard of living typical for Western Europe (or OECD countries). This means another 15 times increase, and by the end of the century after further growth a 40 times bigger economy in the world. Is this possible? Can growth go on forever – still growth is the basis of present modern economy.

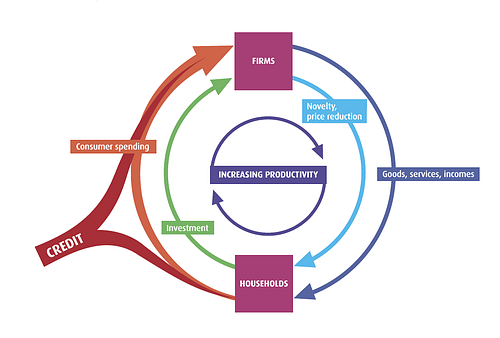

Not surprising when thinking about what happens if there is no growth. Consumption would decrease, companies would not be able to sell their products and would go to bankruptcy, unemployment would mount and so on. The “engine of growth” in market economies allows companies to gain a net profit, which is invested in a development that leads to more growth and jobs. In short, it seems like modern economy has to choose between eternal growth and collapse, both of which are unsustainable. The growth dilemma may be the largest problem for the vision of a sustainable future society.

It is clear that economic growth is crucial up to a point for quality of life, happiness, prosperity, education, health etc. But after that, it appears that economic growth is not so important. In international studies, life expectancy, infant mortality, education, or happiness itself do not increase after a GDP of about 10,000 USD/capita (purchasing power parity using 1995 dollars). In investigations one finds that factors which are important to individual satisfaction and wellbeing do not cost much or cannot be bought at all, such as family, friends, leisure time, enjoying nature etc. Increased income, however, is still a priority in all societies. Why do people rather get richer than happier?

To come to grips with the growth dilemma, we need to ask ourselves which is the role of material possessions. One important aspect is that in society, we tend to judge our prosperity by comparison with others. As long as we are enough equal to our neighbours all is fine, but if they have a better car or even two cars or a nicer house etc. we want the same. Social positioning is the engine of personal ambition and is also fuelling economic growth. It is the social logic behind increased consumption, which the companies need, to develop their businesses, increase profit and – grow!

If economic growth could be unrelated to flows of natural resources, the growth would not be problematic. It could go on forever as long as material consumption does not increase. Increased economy without increasing material flows is called decoupling. Decoupling has been typical for affluent societies, in the sense that economy is growing faster than consumption of resources. The productivity of for example 1 unit of energy (energy intensity) has increased for many years in western societies. But the result of decoupling is offset by an absolute increase in growth, called the rebound effect. We talk about Jevons paradox, meaning that technological progress or efficiency increase, typically leads to increased consumption. We thus have a relative decoupling. On the other hand, absolute decoupling – that the material flow is actually decreasing, while economic growth is increasing – is not seen in our societies.

What kind of solutions do we see for the growth dilemma? One is to dematerialize the economy, that is, an ever-increasing economic value can be given to smaller material things. For example, computers may be quite small and still be very efficient, or that we buy services, for example concerts, much more than material possessions. Much of this has happened. In a modern society, a large proportion of the economy is in the service sector (in Sweden, only about 15% of the workforce is in industry and less than 2% in agriculture and forestry). The efficiency of the production is thus enormous (or relies on imported goods) but it is still offset by increased consumption, and we do not see absolute decoupling.

What kind of solutions do we see for the growth dilemma? One is to dematerialize the economy, that is, an ever-increasing economic value can be given to smaller material things. For example, computers may be quite small and still be very efficient, or that we buy services, for example concerts, much more than material possessions. Much of this has happened. In a modern society, a large proportion of the economy is in the service sector (in Sweden, only about 15% of the workforce is in industry and less than 2% in agriculture and forestry). The efficiency of the production is thus enormous (or relies on imported goods) but it is still offset by increased consumption, and we do not see absolute decoupling.

Another road is green growth. This was a main theme at the 2012 Rio + 20 Conference. Green economy in short only refers to an economy where environmental concerns are taken into account. Here, one component is that material flows become cyclic (recycle all components of products) so that they do not contribute to resource extraction or environmental loads. The economy needs to rely on renewable resources, especially in energy sector. Obviously we need a green sector of the economy, but so far we have not seen it contribute to absolute decoupling. According to the Limits to Growth studies, even very extreme assumptions about technical developments did not in itself solve the problem of limits to growth. They only pushed the peaks further into the future. We have to make lifestyle changes.

As a response to mounting concerns about the growth dilemma, the de-growth movement has developed as a protest against the all-embracing concern with material possessions. The de-growth movement want other ways to measure success. The common practice of using Gross Domestic Product, GDP, as a measure of the success of a country is therefore brought into question. GDP is just the sum of all economic transactions in a country (many of which may be very negative) and was never intended to be a measure of success. The de-growth movement want to focus on welfare, prosperity, or even happiness. See further Chapter 10c.

As a response to mounting concerns about the growth dilemma, the de-growth movement has developed as a protest against the all-embracing concern with material possessions. The de-growth movement want other ways to measure success. The common practice of using Gross Domestic Product, GDP, as a measure of the success of a country is therefore brought into question. GDP is just the sum of all economic transactions in a country (many of which may be very negative) and was never intended to be a measure of success. The de-growth movement want to focus on welfare, prosperity, or even happiness. See further Chapter 10c.

Macroeconomic modelling has been used to explore factors, which might push a capitalist market economy into a steady state, that is non-growth, but still on a high level of prosperity. It turns out that in the common economy, the state or fiscal economy has a large role. Much of the investments are directed to long-term development, such as infrastructure, rather than short-term investments, which are more typical for the private sector. Employment stays on a high level when working hours decrease. No country has tried this recipe, so we do not have practical experience, but the topic is a key point in the British report Prosperity without Growth from 2008.

Materials for session 10b

Basic level

- Read pages 37-46: The Dilemma of Growth in: Prosperity without growth.

- Read pages 29-36: Redefining Prosperity in: Prosperity without growth.

- Read pages 47-58: The Myth of Decoupling in: Prosperity without growth.

Medium level (widening)

- Investigate the character and proposals of the De-growth Movement and science.

- Investigate the possibilities of Green Growth in Chapter 7, pages 67 – 74 Keynesianism and the ‘Green New Deal’ in: Prosperity without growth.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Analyse the possible roads to steady state economy in Macro-economics for Sustainability in: Prosperity without growth, pages 75 – 84.

- Management and politics of a Sustainable Economy in chapters 9 – 11 Flourishing – within limits; Governance for Prosperity; and steps towards a Sustainable Economy, in: Prosperity without growth, pages 85 – 109.

Additional material

Hamilton, J. D. 2012. Oil Prices, Exhaustible Resources, and Economic Growth (from Department of Economics, University of California, San Diego).

References

Jackson, T. 2009. Prosperity without growth: economics for a finite planet. Earthscan.