Välkommen till Svenska Aralsjösällskapet

5c.

Waste – sustainable end-of-life of products

Wastes piling up

Wastes piling up

In the 1970s countries in Europe became alarmed by rapidly growing piles of waste. Landfills were expanding in many countries both by household waste and waste from industries. This was propelled by non-recyclable products from bars, kitchens etc. as well as the increasing number of packages used for all kinds of products in the shops. More than 50% of household solid waste consisted of packages. In the European Union the amounts of household waste is despite efforts over many years still increasing. It is now approaching 600 kg per year and capita.

Even worse is the too common habit of illegal dumping of waste, e.g. along the roads increasing with increasing costs. In addition to being ugly, it pollutes - sometimes seriously e.g. lead or mercury from old batteries - and threatens wildlife. A particular bad habit is to dump waste from ships right into the sea. The sea cannot accommodate all the waste from boats, and many times the waste turns into deadly traps for sea animals, such as seals. Especially plastic is serious since most of the plastic ever produced, non-degradable, is still there and pollutes. In the Pacific Ocean currents have concentrated plastic debris to a huge area called the Trash Vortex.

The costs of the growing piles of garbage and landfills mounted due to increasing land use and other resources being used up. Also landfills were environmentally problematic since they leaked to groundwater and emitted methane, a strong climate gas. For these reasons environmental legislation attempted to limit waste amounts and taxed waste sent to landfill.

An even more important aspect is that waste on landfills is a sign that the resource flow is linear, and therefore completely unsustainable and in fact a symptom of badly designed production and consumption patterns. In general the material flows in Europe were in the 1990s overwhelmingly, more than 95%, linear and going from resources to production, and use to waste.

The largest waste categories are mining and industrial waste. The management of this waste is discussed at Chapter 5a. The most sustainable option is industrial symbiosis when waste is used as a resource. Some wastes are used for building infrastructure (e.g. roads) while agricultural waste may be used for energy purposes. Construction waste is a special case since it is such a large waste category. Costs of waste have spurred building companies to be more inventive to reduce this waste category considerably.

In this sub-session we will mostly address household waste even if many of the options are also valid for industrial and agricultural waste. Another specification is that below we will deal almost exclusively with solid waste. Emissions to water and air, which also may be included in waste, will not be discussed here. There are several ways to deal with the increasing amounts of waste. Below we will summarize the most important ones. These measures should be seen in the contexts of product design (See Chapter 5b) as well as production (See Chapter 5a).

The European Union has listed the different options to deal with waste into a waste hierarchy going from best to worst:

Reduce, or waste reduction, reducing the product flow

Reuse, make products more repairable and with longer lives, or give to next user

Recycle, this most often refers to the materials in the products

Composing, for organic waste, the resulting compost may be used

Fermentation to biogas, also an option for organic waste, and biogas used for energy

Incineration, organic waste may be burned and heat taken care of, e.g. in district heating

Incineration, without recovery of the heat produced

Landfill

The most important way to deal with waste is recycling. Either to recycle the products themselves or the material they consist of. Recycling may be either internal or external.

Recycling bottles is environmental friendly and easy.

Recycling bottles is environmental friendly and easy.

Internal recycling is when in a factory the material discarded in a product step is taken care of and, often after some kind of processing, fed back into the production chain. This is a very important part of Cleaner Production strategies and has reduced waste from industries and increased efficiency considerably.

External recycling, or open loop recycling, is when the material is coming back to the production chain after having been used. A typical case is paper, which is sent back from the consumers after e.g. the newspaper has been used and read. The old paper is then washed to take away ink from printing and used for new paper products. Theoretically a cellulosic fibre can be recycled 6 times before it is too short to be useable for paper. Then it is sent to incineration. This process is also called downcycling, as the quality of the material decreases at each cycle.

Recycling is never perfect but in some cases they may be close to 100%. Thus recycling of lead-containing car batteries is very well organized in some countries to make such a technical recycling loop close enough to perfect to allow the use of the quite toxic lead in society. We would like to see the equally perfect recycling of all kinds of batteries but this is not yet the case.

Recycling of household waste ask for a good waste sorting already in the households themselves. Good household sorting gives 6 basic fractions (compostable, burnable, paper and cardboard, plastics, metal, glass). Of course this has to be followed by proper processing at the later stages, which is not always in place. In addition special waste, such as batteries, light bulbs etc has to be managed in addition to the six categories mentioned.

The many toxic components in different kinds of ordinary household equipments have prompted the European Union and other countries to introduce strict legal requirements on waste management of many products. Best known may be the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment, WEE, Directive. This prescribes how to properly take care of all kinds of electrical and electronic equipment, such as computers, refrigerators etc. It puts large responsibilities on the responsible authorities most often the municipalities. This is however only a small part of the whole. The European strategy for prevention and recycling of waste is one of the presently seven environmental themes in the EU and is backed by the Waste Framework Directive, which includes a long list of special directives.

Recycling is also backed up by economic incentives, most importantly the deposit and refunding system. In this system the customer when buying a beverage pays an amount of money for the bottle or can. He/she is then refunded when the empty bottle or can is returned. In this way more than 90% of aluminium cans in Sweden are recycled.

Increasingly often the producers also are legally required to take care of the wasted products. This is called Extended Producer Responsibility, EPR. In many countries it applies to a large number of electric and electronic products, large equipments such as cars, and equipments with some toxicity, e.g. light bulbs.

Some waste can be bought and sold, that is, it has a market value. Thus scrap metal is quite valuable on the market, and sometimes scrap plastic is also sold. Quite expensive is scrap copper. Also some bio-waste is sold and bought, e.g. forest residues. More recently other products have entered the market, such as used car tires. Of course any kind of used items (cars, furniture etc), which are offered on a market belong to this category, and some municipalities make considerable efforts to make this second-hand market functional. In the waste hierarchy it belongs to reuse.

Recycling reduces the material flows, but also improves energy management as the waste stream includes a considerable amount of energy. This is particularly clear for metals: to produce a metal object from scrap metal rather than from the virgin ore is much less energy requiring. Thus to use scrap iron consumes 6 times less energy, scrap copper 30 times less and aluminium 50 times less energy compared to virgin ore. To use recycled paper instead of fibres from wood uses about 6 times less energy. It is obvious in all cases that virgin resources are saved, for example many trees in the case of paper production. Likewise waste to energy is important: Solid waste is incinerated and the heat used for district heating and coproduction of electricity; compostable waste is fermented to give biogas for energy purposes (See Chapter 2a).

Developments: during the last decade in EU the number of landfills has decreased and those remaining are strictly regulated and are subject to the IPPC Directive (Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control). Instead waste stream are managed according to increasingly more careful legal control. Recycling is increasing and material which cannot be recycled are more often sent to waste incineration in power plants for energy recovery. Still, amounts of household solid waste per capita continue to increase.

Materials for session 5c

Basic level

- Read Environmental Science, chapter 18, pages 551-555: Solid Waste.

- Read Environmental Science, chapter 18, pages 556-558: Solid Waste Management.

- Read Environmental Management, book 3, chapter 10: Waste Management and Product Design.

- Read Environmental Management, book 2, chapter 10: Waste Reduction.

Medium level (widening)

- Read Environmental Science, chapter 18, pages 558-562: Soil Protection and Solid Waste Management.

- Read Environmental Management, Book 1, pages 208-209, part B: European Union Environmental Legislation.

- Read Environmental Management, Book 1, pages 211-212, part B: European Union Environmental Legislation.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Study Environmental Management, book 4, case1: Kunda Nordic Tsement.

- Study some cases which use the C2C (Cradle to Cradle) approach, e.g. McDonough Braungart Design Chemistry MBDC.

References

Klemmensen, B., Pedersen, S., Dirckinck-Holmfeld, K.R., Marklund, A. and L. Rydén. 2007. Environmental Policy - Legal and Economic Instruments. Book 1 in a series on Environmental Management. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

Nilsson, L., Persson, P. O., Rydén, L., Darozhka, S. and A. Zaliauskiene. 2007. Cleaner Production - Technologies and Tools for Resource Efficient Production Book 2 in a series on Environmental Management. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

Rydén. L., Migula, P and M. Andersson. 2003. Environmental Science - understanding, protecting, and managing the environment in the Baltic Sea region. Baltic University Press. Uppsala, Sweden.

Weiß, P. and J. Bentlage. 2006. Environmental Management Systems and Certification. Book 4 in a series on Environmental Management. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

Zbicinski, I., Stavenuiter, J., Kozlowska, B. and H.P.M. van de Coevering. 2006. Product Design and Life Cycle Assessment. Book 3 in a series on Environmental Management. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

6a.

The living world

The many millions of life forms on our planet form the basis of all life and our future. Sorry to say, the most obvious impact of the growing human society is reduced biodiversity, the diversity of life forms. For many, the beginning of work for a sustainable future was a growing concern for so many threatened species and environments. The alarm clocks were first rung by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, IUCN (today called International Conservation Union) and soon after by the World Wildlife Fund, WWF, already after the Second World War. Diversity decreases on three levels: genes, species, and ecosystems.

Today, the threats towards our living world are even more serious. The extinction of species is estimated to be between 100 and 1000 times faster than before the big impact of human societies. Behind this are three main and many minor changes. Firstly; the ongoing disappearance of natural environments, biotopes, the most serious being tropical forests, coasts, and wetlands. Secondly; the spreading of species to environments where they did not exist before, not the least marine species, which travel with the water of big ships. These new alien species most are often not able to establish themselves, but some grow without control and become invasive and destroy existing ecosystems. Thirdly; pollution may be disastrous to species, which are sensitive to chemicals for which they do not have any defence.

The different life forms have a large value to humans, not always recognized. They form the base for our production of food and many species are the origin of pharmaceuticals, which form the base for healthcare and our capacity to cure diseases. The efforts to preserve genetic diversity have taken the form of gene banks, where species threatened by extinction are stored for the future. The value of a living and rich environment allows us to enjoy nature and its beauty. A green and natural environment is important for our wellbeing, as has been shown repeatedly in much research.

The services which nature provides to societies and in general to the planet are called ecosystems services. The ecosystems services are productive, such as growing of food, or regulatory, such as natural cleaning of water or pollination of plants or regulation of weather. There are also aesthetic ecosystems services such as the beauty of nature or individual species and our possibilities to enjoy nature. Some of these ecosystems services are today drastically decreasing, e.g. the pollination of fruit trees is very bad in some areas, with grave economic consequences, due to diminishing populations of pollinating insects.

The services which nature provides to societies and in general to the planet are called ecosystems services. The ecosystems services are productive, such as growing of food, or regulatory, such as natural cleaning of water or pollination of plants or regulation of weather. There are also aesthetic ecosystems services such as the beauty of nature or individual species and our possibilities to enjoy nature. Some of these ecosystems services are today drastically decreasing, e.g. the pollination of fruit trees is very bad in some areas, with grave economic consequences, due to diminishing populations of pollinating insects.

A complete review of the state of the planet's ecosystems was initiated by the UN in the year 2000. More than a thousand researchers all over the world contributed to the report published in 2005, the Millennium Ecosystems Assessment, MA. They concluded that 60% of the ecosystems are in decline, some of them seriously so. The Assessment is seen as complementary to the reports by the Climate Panel and will be continued.

The traditional way to safeguard biological diversity and protect individual species from extinction is nature conservation efforts. This includes protection of parts of the landscape as national parks or through similar arrangements. The EU system Natura 2000 with many thousands of individual sites together protects around 18% of the land in the EU countries. These include all kinds of states of protection. Important parts of the system are sites for the protection of birds and wetland areas. The IUCN has established a red list of species in different degrees of threatening. Red listed species are being protected in many countries.

The UN Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD) from the 1992 Rio Conference is a most important initiative to protect our living world. Today, the convention has 192 nations and the European Union as partners. The convention covers all ecosystems, species, and genetic resources. At its COP 10 in Nagoya, Japan, in October 2010 a Protocol on sharing of genetic resources was agreed on. The COP 11 was organized in Hyderabad in India in 2012. A number of other agreements exist, but the results from these are weak and implementation is often lacking. To strengthen the process, the UN announced the period 2011-2020 to be a decade for biodiversity.

The concept of Ecosystems health has recently gained support as an integrated concept describing the interlinked issues of biodiversity, ecosystem services and carrying capacity. A healthy ecosystem includes plants and animals that produce organic matter and simple organisms that break it down. A healthy ecosystem has a large diversity and is capable of self-restoration after external disturbances (resilience). The ecosystem health concept frequently also includes concern for human health and good agricultural practices, as humans are seen as part of the ecosystem. The concept includes a dimension of philosophy (see e.g. the Gaia philosophy) and ethics (for example deep ecology) and respect for life forms.

Materials for session 6a

Basic level

- Read Environmental Science, chapter 8, pages 240-246: Changing the Living World.

- Read Environmental Science, chapter 8, pages 247-251: Changing the Living World.

- Read Environmental Science, chapter 7, pages 206-211: Society and Landscape.

Medium level (widening)

- Read Environmental Science, chapter 8, pages 222-239: Changing the Living World.

- Read Ecosystem Health and Sustainable Agriculture, book 3, chapter 2, pages 39-51: Landscape Functions and Ecosystem Services.

- Read the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) Synthesis Report, pages 16-54 (pdf-file).

- Study Difference Between a Biome & an Ecosystem in Sciencing.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Study the Convention of Biological Diversity, CBD.

The official Convention of Biological Diversity website.

The IUCN website. - Study the IUCN world conservation strategy (pdf-file).

- Study the concept of Ecosystems Health as applied to the Baltic Sea in the report Ecosystem Health of the Baltic Sea (pdf-file) of Helcom (Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission).

References

Karlsson, I. and L. Rydén (eds.) 2012. Rural Development and Land Use. Ecosystems Health and Sustainable Agriculture: Book 3, Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

Reid, W. V. et al. 2005. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Synthesis Report. Island Press.

Rydén. L., Migula, P and M. Andersson. 2003. Environmental Science – understanding, protecting, and managing the environment in the Baltic Sea region. Baltic University Press. Uppsala, Sweden.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

6b.

Land and water

We all live on and by the land and the water of planet Earth. To care for land and water, so it may host us and feed us, is an important part of sustainable development. The surface of our planet has some 30% of land, some green and productive; others less so, like mountains and deserts, glaciers and tundra. All of these are dramatically changing: forests are shrinking; deserts are spreading and glaciers melting. The Global Footprint network estimates that there are 12.5 billion so-called global hectares, that is, bio productive land areas. This means there are 1.78 global hectares per capita to produce our food, energy, and fibres and to take care of our waste. The per capita global hectares are decreasing, both due to population increase and the destruction of land.

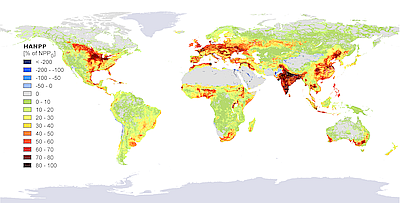

In the western world we see an overuse of land. Human activity dominates 43% of the land surface of the Earth, and we affect twice that area. One-third of all available fresh water is diverted to human use. A full 20% of the net terrestrial primary production of the Earth, the sheer volume of life produced on land every year, is harvested for human purposes. We use more than our fair share of bio productive land, in Europe about 3 times more and in the US 5 times more (see further Session 4). The Global South use much less resources, but this situation still constitutes an overexploitation of natural resources, especially of fossil energy and forests. Land resources start to become scarce, and we may expect a lack of food in the world in the future. This is corroborated by a steeply increasing price of both food and land and by accelerated foreign investments in land, especially in Africa (land grabbing).

In the western world we see an overuse of land. Human activity dominates 43% of the land surface of the Earth, and we affect twice that area. One-third of all available fresh water is diverted to human use. A full 20% of the net terrestrial primary production of the Earth, the sheer volume of life produced on land every year, is harvested for human purposes. We use more than our fair share of bio productive land, in Europe about 3 times more and in the US 5 times more (see further Session 4). The Global South use much less resources, but this situation still constitutes an overexploitation of natural resources, especially of fossil energy and forests. Land resources start to become scarce, and we may expect a lack of food in the world in the future. This is corroborated by a steeply increasing price of both food and land and by accelerated foreign investments in land, especially in Africa (land grabbing).

In addition, productive land is decreasing. Present land management practices decrease productive land and leads to loss of topsoil and desertification. It is estimated that the loss of topsoil is several hundred times larger than the build up of new soil and new organic content. Global warming in some areas leads to dramatically decreased precipitation and extensive droughts, making large areas unfit for production. In addition, land management practices increase emissions of GHG, especially carbon dioxide. Carbon is released through drainage of wetlands, ploughing, and all procedures, which increase the access to air, and oxidation of the organic content of topsoil.

In addition, productive land is decreasing. Present land management practices decrease productive land and leads to loss of topsoil and desertification. It is estimated that the loss of topsoil is several hundred times larger than the build up of new soil and new organic content. Global warming in some areas leads to dramatically decreased precipitation and extensive droughts, making large areas unfit for production. In addition, land management practices increase emissions of GHG, especially carbon dioxide. Carbon is released through drainage of wetlands, ploughing, and all procedures, which increase the access to air, and oxidation of the organic content of topsoil.

The availability of water is equally shrinking. The overuse of surface water e.g. for agriculture, which represents 70% of water use, has lead to sinking groundwater tables, sinking water levels of the large lakes, such as the Aral Sea in Central Asia, Lake Victoria in East Africa, and also dramatic changes of the largest rivers, e.g. Colorado River in North America. Melting glaciers give less water to the rivers and thus influence agriculture in the drainage areas.

The interface between land and sea is especially critical. Many coastal areas are threatened by pollution and most seriously eutrophication, that is, an oversupply of nutrients, nitrogen, and phosphorus. The nutrients stimulate the growth of algae, which consumes available oxygen and may lead to anoxic bottoms devoid of all higher life forms. In this way coastal areas in Southeast Asia, crucial for the food for billions of inhabitants, are destroyed, as are thousands of lakes and rivers in the world.

The interface between land and sea is especially critical. Many coastal areas are threatened by pollution and most seriously eutrophication, that is, an oversupply of nutrients, nitrogen, and phosphorus. The nutrients stimulate the growth of algae, which consumes available oxygen and may lead to anoxic bottoms devoid of all higher life forms. In this way coastal areas in Southeast Asia, crucial for the food for billions of inhabitants, are destroyed, as are thousands of lakes and rivers in the world.

Most of the surface of the planet 70%, covered by water, makes up the seas of the world. Also, these are severely changed. The productive capacity of the seas of the world is reduced both by these changes in the conditions of the environment and also by over harvesting, especially of fish. The world oceans are furthermore facing increased acidification due to increased concentrations of carbon dioxide turning into carbonic acid when dissolved in the water. So far, about 50% of CO2 emissions have been dissolved in the oceans. The changes are especially serious to coral reefs, very special ecosystems that harbour some 50% of marine biodiversity.

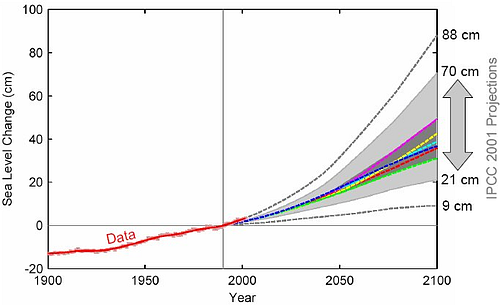

In the long term, coastal areas face yet another difficulty. Due to global warming, sea levels will rise. According to predictions of climate models, low-lying coastal areas, for example in Southeast Asia, will be flooded as this will happen towards the end of this century.

In the long term, coastal areas face yet another difficulty. Due to global warming, sea levels will rise. According to predictions of climate models, low-lying coastal areas, for example in Southeast Asia, will be flooded as this will happen towards the end of this century.

Several measures to safeguard land and water have been introduced. Landscape protection, included as one measure in the Biodiversity Convention, cover about 20% of all land surfaces on Earth. Improved land management measures, such as agroforestry, minimum tillage or use of bio char, have also been implemented to keep topsoil intact and retain the productive capacity of land, e.g. in several projects in Asia and Africa. Tree plantation is done on a large scale in many places, both for climate mitigation and to improve ecosystem services. New techniques for irrigation in agriculture may dramatically reduce the need for water. Most importantly, restoration of ecosystems is possible also at large scale and in areas severely degraded and barren. Such restoration projects demonstrate how soil, greenery, and water can return, people get new livelihoods as food production, economic life and wellbeing is strengthened.

Of the international conventions introduced to protect land and water of the world, the most significant are the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, UNCCD. It is regrettably the weakest of the Rio conventions, as it is lacking its own financing. Agreements on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) are included in the Climate Convention, as it has a great influence on GHG emissions. Wetland preservation is covered by the already old Ramsar convention. This convention is focused on the preservation of biodiversity rather than on the productive capacity of land and water. There is no convention to protect the oceans of the world, which thus face e.g. unregulated fishing, in addition to e.g. dumping of waste, most seriously plastics which remain in the water. EU directives protect landscape, meadows, and surface waters.

The landscape with its land and water, forests and fields, are of immense importance for the wellbeing of us humans, not only for its physical services such as providing food and water, but also as a living environment, for its cultural and spiritual significance, and as the means by which we are connected to the past and the future of humankind. We should leave planet Earth to our children and grandchildren to enjoy just as much as our ancestors and we have.

Materials for session 6b

Basic level

- Read Environmental Science, chapter 7, pages 187-195 and 196-201: Society and Landscape

- Study the basics of footprint science on Global Footprint Network homepage.

Medium level (widening)

- Read Water Use and Management, chapter 1: Water Resources and Water Supply.

- Land Resources planning (LRP) to address land degradation and promote sustainable land management (pdf-file). Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations.

- The world's remaining great forests by Jessica Aldred, the Guardian.

- Wikipedia: Biome.

- Living Planet Report 2022.

- The Baltic Sea, a film by Markus Nord (YouTube film).

- Green Gold – Environmental filmmaker John D. Liu documents large-scale ecosystem restoration projects in China, Africa, South America and the Middle East, highlighting the enormous benefits to people and planet of undertaking these efforts globally (YouTube film).

Advanced level (deepening)

- Study Desertification and the UNCCD by Phillip Cullet, University of London, and at the home page of the UNCCD.

- Study Deforestation: Facts, Causes & Effects at Livescience.

References

Grooten, M. (ed.). 2012. Living Planet Report 2012 – Biodiversity, biocapacity and better choices.

Lundin, L. C. (ed.) 2000. Water Use and Management. Sustainable Water Management book 2. Baltic University Programme, Uppsala.

Rydén. L., Migula, P and M. Andersson. 2003. Environmental Science – understanding, protecting, and managing the environment in the Baltic Sea region. Baltic University Press. Uppsala, Sweden.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

6c.

Agriculture and food

The production, storage, distribution, eating, and management of food constitute one of the most important human impacts on the environment. At the same time, it is a most essential part of our everyday life and wellbeing. Agriculture covers 40% of the earth's total ice-free land area. It accounts for 70% of the global fresh water use, it emits more greenhouse gases than any other human activity, it employs 3/4 of the world's poorest people, and it feeds all of us. Agriculture is the key foundation of human civilization, and it is also where most of our present day development problems converge, such as poverty, hunger, environmental degradation and climate change.

Agriculture has developed dramatically. The production and care taking of harvesting, hunting, and fishing once was the main occupation in society. In a modern industrialized country, however, only some 2-5% of the population provides all food for the rest. Agriculture and fishing has been industrialized. The production from a hectare of land has been multiplied by new methods, new genetic varieties, and input of nutrients. These developments are still ongoing, e.g. using GMOs, genetically modified organisms. The GMO technique is by itself not a threat to sustainability of the environment; it is just a method.

Industrialized agriculture depends on linear material flows of nitrogen and phosphorus, which is unsustainable. Phosphorus, mined from a few deposits in the world, will as a non-renewable resource finally become emptied. Nitrogen produced by the industrial fixation of nitrogen gas requires large input of fossil energy and is thus also in this way non-renewable. The global nitrogen flow has due to this doubled and is unsustainable. Excess nitrogen and phosphorus from agriculture is today polluting the water in lakes, coasts, and the sea in many parts of the world, and it is causing serious eutrophication.

In contrast, traditional agriculture was carefully managing the circulation of nutrients by returning manure to the fields, composting all organic waste from the preparation of food, and also by returning human excrement to farmland. Among the many efforts made today to re-establish circular flows of nutrients, we see how manure, directly or as a residue after biogas production containing most nutrients, are being returned to fields; food waste in cities is collected; and sludge from wastewater treatment plants is used for fertilization. But it is insufficient and heavy metals and toxic organic chemicals too often pollute organic waste, e.g. sludge from wastewater treatment plants.

Modern agriculture produces an ever-increasing share of meat rather than grains and vegetables. In an industrial society, 80% of all we see growing on farmland is food for animals, and large parts of land are used as grazing land for animals. Meat in the menu has been increasing worldwide during the last 100 years, and in the western world it is still increasing. This is clearly unsustainable and in the future meat in our diet has to decrease significantly. The carbon footprint of one kg of beef is a hundred times that of a kg of potatoes. The excessive production of cheap meat depends on factory-like conditions, violating animal welfare. This is unethical, and it also leads to low quality food. Today in some countries it is increasingly limited by regulations.

In the western world, wasting food adds to the problem. In the EU, about 30% of all edible food is wasted, and in the US about 50%. In the US food costs are the lowest, wasting of food the highest and animal rights least respected. An important strategy to reduce the carbon footprint of food is to take care of food better and to reduce meat in the human diet.

In the Global South a major problem is that a high percentage of food is destroyed in storage, e.g. by mould and rodents, and that food is not distributed to those who needs it.

Seafood is an important part of the diet. Once, most human societies were located along coasts or rivers to secure seafood, fish, crabs, etc. Today also fishing has been industrialized, with partly terrible consequences. With modern trawls, sonars and refrigeration ships the seas have been vacuum cleaned; global peak fish occurred in the end of 1990s and several, formerly common fishes are today threatened species, e.g. tuna, swordfish, and eel. Regulations using fishing quotas have been introduced in many waters and have today led to the improvement of fishing in some European waters. It is a modern application of management of a common resource to avoid the tragedy of the commons (See Chapter 9). Aquaculture, especially of salmon, has increased dramatically, but as long as they are fed with fish from the sea it is not a sustainable practice.

Some new approaches have been introduced to increase self-sufficiency and food security. Organic farming and food is increasing rapidly in many places in the world. It relies on circulation of nutrients, limited or no-use of biocides, and secured animal welfare. In agroforestry, agriculture is conducted among trees, a system which preserves soil and water and is building new topsoil. Growing food in cities, urban agriculture, uses terraces, roofs and other areas to grow food. Most advanced is permaculture, which builds on ecological design principles, including growing your own organic food, use more rainwater, preservation of landscapes, restoration of ecosystems, and homes built from natural materials.

Food is a global commodity. This is in most cases not a serious concern as such, but it carries a transportation cost. An opposite trend is to increasingly buy food on local markets and from local producers. It leads to a more seasonal diet, often with higher quality and less cost for preservation.

Will there be enough food in the future? How will 9 billion people be able to eat without undermining the very basis for food production? The problem is aggravated by competition between food and energy crops, as well as the continuing degradation of agricultural land. Key changes are needed in this sector to achieve a transition to a sustainable society.

Materials for session 6c

Basic level

- Read A Sustainable Baltic Region, session 4, chapter 1: Land and Productivity – Can the Baltic Region Feed Us All?

- Read A Sustainable Baltic Region, session 4, chapter 6: Approaches to Sustainable Agriculture – Ecological Farming.

- Read EHSA, book 1, chapter 33: Carbon Flows and Sustainable Agriculture.

- Read Urgent Call to Reduce Food Waste in the EU by Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development.

Medium level (widening)

- Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education Program. A program of UC Agriculture & Natural Resources, University of California, Davis, USA.

- Read EHSA Book 1, chapter 8, pages 65-81: Leaching Losses of Nitrogen from Agricultural Soils in the Baltic Sea Area.

- Read EHSA Book 1, chapter 27, pages 259-276: Consumer Demands: Organic Agriculture in Sustainable Agriculture.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Study food losses in Global Food Losses and Food Waste – Extent, Causes, and Prevention. Report to the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 2011.

- Read How to Feed the World in 2050?. Report from a FAO convened three-day Meeting of Experts in Rome, 2009.

- Read World Review of Fisheries and Aquaculture. UN Food and Agricultural Organization, 2010.

References

Ebbersten, S. and B. Bodin. 1997. Food and Fibres – Sustainable agriculture and forestry. A Sustainable Baltic Region. Session 4.

Jakobsson, C. (ed.) 2012. Sustainable Agriculture. Ecosystem Health and Sustainable Agriculture, Book 1. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

6d.

Forests and fibres

Forests cover a substantial part of the land surface of the earth. In Europe, it is 44%, a figure that in Sweden and Finland increases to about 70%. About half of the forests in the world have been cut down during the development of human societies. Deforestation is still going on, now mostly in the Global South. This is serious since the tropical forests harbour a large part of the world’s biodiversity (See Chapter 6a). The boreal forests in Northern Europe are more monotonous.

Much of the existing forests have changed due to human intervention and are today more like monocultures, in the north of pine trees, and in the south of other economically interesting trees such as oil palm or fast-growing eucalyptus. In Europe, the only residues of the original large forest, which covered the continent, are found in Belarus and Poland. Nevertheless, forests remain an important part of the landscape and provide all kinds of ecosystems services (See Chapter 6a).

Forests are important for sustainable development. They can function both as sinks or sources of CO2 and other GHGs, and are thus an essential part of the climate change and the efforts to mitigate climate change (See Chapter 4b). Forests are growing slowly and for that reason they naturally bring in the issue of long-term management of a renewable resource. Concern for forest and forest survival led to the concept of sustainable development already in the 18th century (See Chapter 1a). Forests are a key natural resource for human society.

Forests constitute a renewable source of energy, a fuel. Wood was once the only source of energy in most societies. The excess harvesting of trees and bushes for cooking etc in some developing countries is a threat to proper land development. In western countries, wood as a source of energy takes several forms. Most important is traditional wood, but to that is added also wood waste or forest residues, such as branches and roots. The pulping liquor, or black liquor, from the processing of pulp, paper, and paperboard in industry represents about 50% of the material in wood. It contains lignin, which cannot be used for paper manufacturing. Waste paper and wood from constructions as well as residues from saw mills and other industries etc can be used as energy for example in district heating.

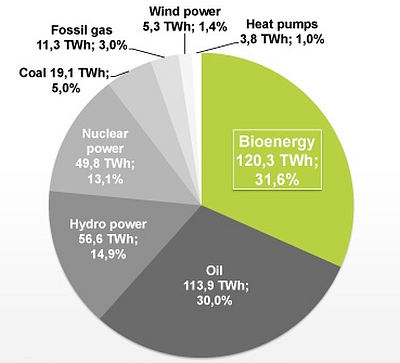

The use of bio energy in the energy mix of the EU and its member states is increasing. (See Chapter 4a). In Sweden, the figure is 32% and increasing. Wood biomass as pellets and wood chips is used in burners in individual homes and in power plants. Black liquor can be used directly, but is increasingly converted into biodiesel. So-called second generation biofuels rely on cellulose from wood being hydrolysed and subsequently fermented into ethanol. Paper and wood waste is burned in household waste incineration plants to produce heat and electricity.

Energy forests, also called short rotation plantations, are plantations of fast-growing species, e.g. Salix. They are harvested after 3–5 years, having reached a height of about 5–6 meters. Energy forest still represents only a small part of the bio energy market.

Wood is foremost a material for all kinds of constructions, from small objects to furniture and buildings. The technology of using sawed timber for building houses has improved dramatically during the last 20 years. Multi-storey and multi flat houses may today be built entirely by wood. This is an improvement compared to the use of concrete and plastics. Concrete production is causing some 5% of the world's CO2 emissions and need to be reduced. The transport of wood to the building site requires fewer efforts and energy, since wood is much lighter. The building time is also shorter for wooden houses, all making wood houses better economy. Finally, the end-of-life of a wooden building does not constitute a problem.

Wood is also the main source of fibres and chemicals used in all kinds of material. Most important is the production of paper, which uses the cellulose fibres in the wood, but also e.g. for insulation materials. The forest will also have to replace fossils for manufacturing. In a future without oil, the chemical industry (the largest industry sector in the EU) will need renewable sources for production of chemicals, including wood, to develop an entirely green chemistry.

Materials for session 6d

Basic level

- Read EHSA, book 3, chapter 13, pages 166-170: Sustainable Forestry.

- Read EHSA, book 3, chapter 17, pages 197-202: Biomass Production in Energy Forests.

- Study Białowieża National Park, the original European Forest.

Medium level (widening)

- Read EHSA, book 3, chapter 14, pages 171-178: Forestry in the European Union Parts of the Baltic Sea Region.

- Read EHSA, book 3, chapter 15, pages 177-186: Forests and Forestry in Three Eastern European Countries.

- Read Land Areas and Biomass Production for Current and Future Use in the Nordic and Baltic Countries (pdf-file) by Nordic Energy Research (NER) research project.

- The World's Remaining Great Forests by Jessica Aldred, the Guardian.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Study multi-story wooden houses. Resources include: Multi-Story Timber Building in UK and Sweden. In NZ Timber Design Journal.

- Global Forest Watch – Forest monitoring designed for action.

References

Karlsson, I. and L. Rydén (eds.). 2012. Rural Development and Land Use. Ecosystem Health and Sustainable Agriculture: Book 3. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

Sida 8 av 15