Välkommen till Svenska Aralsjösällskapet

8b.

Welfare

A sustainable society needs to secure human welfare. Welfare is very multidimensional and in addition different for each person, and it also depends on the society. Basic is security, health, and justice; to secure basic needs such as food; and access to education and work opportunities. Human welfare will be touched upon here and in several other sessions, in particular see also Chapter 8c, and Chapter 10 b. Welfare is an important component of the social dimension of sustainable development. Here we will attempt to define what is included in basic needs and rights. This is not similar to resource flows and other physical and biological conditions, and we will have to rely on norms, that is ethics, as first principles, rather than laws of nature.

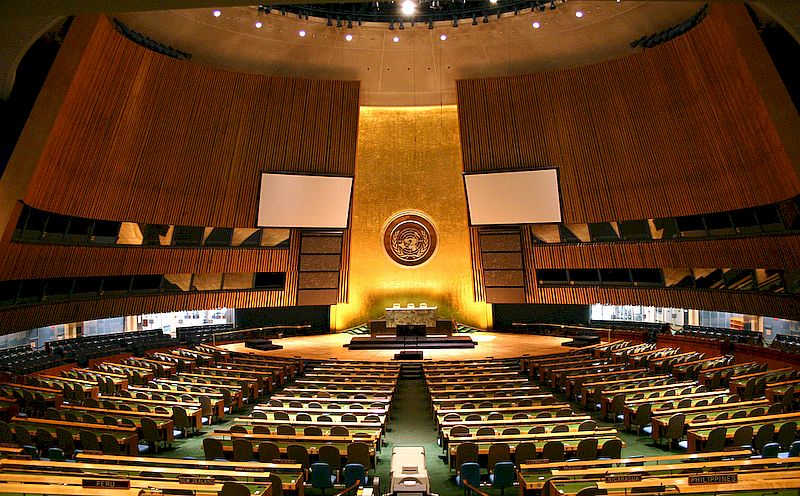

A first principle is the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1948. The background was the atrocities carried out during the Second World War and the need for a document establishing which values that should not be violated regardless of circumstances. It is interesting to note that the Earth Charter (not yet adopted by the UN) can be seen as an extension of the Declaration, to encompass not only humans but also all other living beings and all Nature. The General Declaration of Human Rights have been followed by several other documents e.g. on children’s rights, workers’ rights etc. The UN system has thus played, and still plays, an important role in establishing a global ethics.

The Declaration includes a number of freedoms and rights, which had been included in different declarations since the American Declaration of independence of 1776 and French Revolution of 1789. These include religious freedom, political freedom (right of speech); to this was later added sexual freedom. There are also inscribed equal rights between genders, between different ethnic groups and rights for minorities. Each human individual should thus be respected and his/her integrity protected regardless of physical, ethnic or social belonging. The Declaration of Independence says "all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness".

The Declaration includes a number of freedoms and rights, which had been included in different declarations since the American Declaration of independence of 1776 and French Revolution of 1789. These include religious freedom, political freedom (right of speech); to this was later added sexual freedom. There are also inscribed equal rights between genders, between different ethnic groups and rights for minorities. Each human individual should thus be respected and his/her integrity protected regardless of physical, ethnic or social belonging. The Declaration of Independence says "all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness".

It is obvious that these rights have not been implemented fully in any state, although differences between states are large. Especially should be mentioned that minority rights are violated repeatedly as majority groups attempt to secure their own power and privileges, which in the worst case can lead to ethnic cleansing. Gender rights are violated in many cultures where it is not customary that women decide for themselves, for their future, choice of husband or profession, and violence against women are common.

The United Nations General Assembly adopted the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) in 1966. The ICESCR, which went in force in 1976, commits its parties to work toward the granting of economic, social, and cultural rights (ESCR) to individuals, including labour rights and the right to health, the right to education, and the right to an adequate standard of living. In 2011, the Covenant had 160 parties. The covenant should be seen as a political agreement on basic duties of a modern welfare state and is thus different from the Declaration of Human Rights – which is perceived as a global ethics always valid regardless of circumstances – although it has a similar background.

In the declaration it is assured that each human has the right to safety and health, to education and possibilities to support themselves. These three parts of a human life – care when being child or elderly; education in childhood and young years; and work to have an income and livelihood – are the basic concerns for social security. A modern welfare state safeguards social security by social insurance programs and provides socials services in case of poverty, old age, disability, unemployment, and others. The means include retirement pensions, disability insurance, and unemployment insurance, to guarantee that each citizen has access to necessities such as food, clothing, housing as well as medical care and social work. The right to social security is recognized both in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Convent on Economic, Social and Cultural rights.

In the declaration it is assured that each human has the right to safety and health, to education and possibilities to support themselves. These three parts of a human life – care when being child or elderly; education in childhood and young years; and work to have an income and livelihood – are the basic concerns for social security. A modern welfare state safeguards social security by social insurance programs and provides socials services in case of poverty, old age, disability, unemployment, and others. The means include retirement pensions, disability insurance, and unemployment insurance, to guarantee that each citizen has access to necessities such as food, clothing, housing as well as medical care and social work. The right to social security is recognized both in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Convent on Economic, Social and Cultural rights.

Not everyone can easily adjust to society. A certain percentage (estimated to be about 7% in some societies) suffer from minor or major physical, mental or social handicaps. Also, these individuals need to be taken care of. A smaller or sometimes larger sector of the population live their lives outside established norms. We have crimes; use of drugs, alcoholism; or simply individuals staying outside the established society. Each society has mechanisms to deal with these individuals; but again one should emphasize that also here basic human rights should be respected.

Materials for session 8b

Basic level

- History of Universal Human Rights up to WW2 by Moira Rayner.

- The Creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by Peter Bailey.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 40: Population and Living Standards.

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 42: Women and Gender in History in the Baltic Region.

Medium level (widening)

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 44: Work and Unemployment.

- Read EHSA, Book 3, chapter 9: Economic Development and Work Opportunities in Rural BSR.

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 45: Use and Abuse of Tobacco, Alcohol and Narcotics – a Baltic Dilemma.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Examine how your country’s social security is organized.

References

Karlsson, I and L. Rydén (eds.). 2012. Rural Development and Land Use. Ecosystem Health and Sustainable Agriculture: Book 3. Baltic University Press. Uppsala.

Maciejewski, W. (ed.) 2002. The Baltic Sea Region – Cultures, Politics, Societies. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

8c.

Social sustainability, happiness and the one-planet-life

What do we mean by socially sustainable? Leanne Barron and Erin Gauntlett at Murdoch University of Western Australia say that “Socially sustainable communities are equitable, diverse, connected and democratic and provide a good quality of life.” Is this possible? Will basic human needs be satisfied in a society where the outer conditions is determined by the carrying capacity of the planet and the possibilities of other life forms to thrive as well? Will the inhabitants of a sustainable society be happy and well, or poor and needy? In this sub-session we will examine issues related to the individual. In Chapter 9 on the The political dimensions of sustainability we will look at the issues from the perspective of the society.

The transition to a sustainable society requires that we live a one-planet-life. We need to reduce our consumption of resources to those available in the long term, to the carrying capacity of the planet. This will certainly include a number of technical adjustments, such as houses needing less heating, and cars not running on fossil fuels. But it will also require changes in lifestyles. An example is the Swedish family, which experimentally got all the technical devices in a new house (low energy house with solar panel and PV cells) to live a low carbon life. When it was time for ski vacation the air trip to the Alps was not allowed within the carbon budget. They had to take the train to the Swedish mountains. Not necessarily worse, but a change. Nor was it possible to use the private car for commuting to work, but rather public transport and biking, and they had fewer dinners with steaks, and had to be more careful with waste sorting.

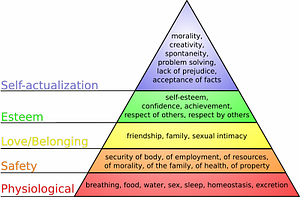

Basic human needs have been much researched. The model proposed by American psychologist Abraham Maslow already in the 1940s includes five levels of needs: first physiological needs, such as food, water and air; next the individual's safety and security such as personal security, financial security, health and well-being; thirdly social needs including feelings of belongingness, friendship, intimacy, and family; fourth, the need to be respected and to have self-esteem and self-respect; and finally self-actualization: “What a man can be, he must be”. Viktor Frankl, with experience from the holocaust, later added self-transcendence, spiritual needs. Chilean philosopher Manfred Max-Neef, as well as others, have later criticized the level structure and argued that fundamental human needs are non-hierarchical.

Basic human needs have been much researched. The model proposed by American psychologist Abraham Maslow already in the 1940s includes five levels of needs: first physiological needs, such as food, water and air; next the individual's safety and security such as personal security, financial security, health and well-being; thirdly social needs including feelings of belongingness, friendship, intimacy, and family; fourth, the need to be respected and to have self-esteem and self-respect; and finally self-actualization: “What a man can be, he must be”. Viktor Frankl, with experience from the holocaust, later added self-transcendence, spiritual needs. Chilean philosopher Manfred Max-Neef, as well as others, have later criticized the level structure and argued that fundamental human needs are non-hierarchical.

From a sustainability perspective it is relevant to observe that none of these needs refer to having many things, consumerism, or travelling over the world, or other parts of modern life which consumes many resources. Also in research on energy use it is clear that what people appreciate the most consumes least energy. Thus being with friends and family or the loved one does not cost much energy, while daily commuting to work, which takes much energy, is not popular. The the world's carrying capacity may then be enough for all of us. Mahatma Gandhi in a famous statement ones said: “The world has enough for everyone’s need, but not enough for one person’s greed”, when talking on a society based on Sarvodaya — the well-being of all.

The recently developed happiness research stresses that numerous studies have clearly shown that subjective well-being and material wealth are only loosely coupled. Perceived well-being in western industrialised countries peaked around 1970 or so, while economic development and resource use has continued to increase without resulting in any increase in perceived well-being (See also Chapter 10b). Immaterial factors which contribute to quality of life – such as leisure, having meaning and purpose, relationships, social participation and self-fulfilment – become more and more important. The research area ‘Sustainable Quality of Life’ of Sustainable Europe Research Institute (SERI) stresses these positive relations between sustainable development and a high quality of life. If sustainable development policies and strategies want to be successful, they have to influence our quality of life in positive ways.

The recently developed happiness research stresses that numerous studies have clearly shown that subjective well-being and material wealth are only loosely coupled. Perceived well-being in western industrialised countries peaked around 1970 or so, while economic development and resource use has continued to increase without resulting in any increase in perceived well-being (See also Chapter 10b). Immaterial factors which contribute to quality of life – such as leisure, having meaning and purpose, relationships, social participation and self-fulfilment – become more and more important. The research area ‘Sustainable Quality of Life’ of Sustainable Europe Research Institute (SERI) stresses these positive relations between sustainable development and a high quality of life. If sustainable development policies and strategies want to be successful, they have to influence our quality of life in positive ways.

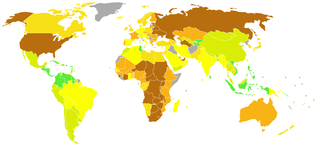

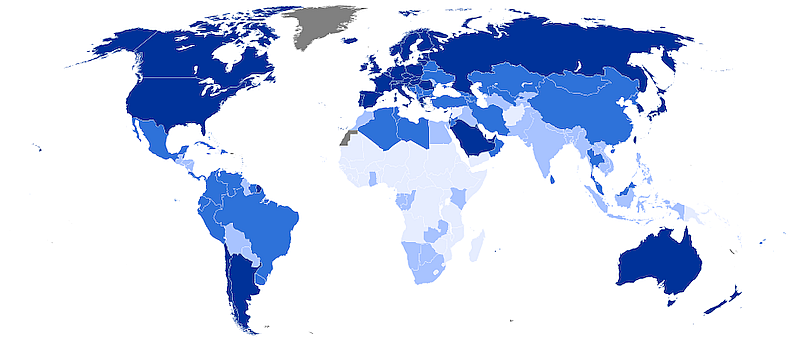

There are several indices to monitor human wellbeing. Most established might be the United Nations Human Development Index, HDI, which includes the three indicators child survival, purchasing power and education. Values of HDI are available for most countries in the world. A sustainable society is seen as a society where human well-being is high enough (HDI > 0.8) and ecological footprint low enough (<.1.8 global ha/cap) (See www.footprintnetwork.org). Other more developed indices include the Weighted Index of Social Progress, WISP, by Richard Estes to measure the amount of well-being in different societies, which uses up to 40 different indicators.

To measure of the development of a country most countries use the Gross Domestic Product GDP, which is the total economic turnover, but several alternatives have been proposed. The Genuine Progress Indicator, GPI measures whether a country's growth, increased production of goods, and expanding services have actually resulted in the improvement of the well-being of the people. In GPI negative costs, such as costs for environmental impacts, are subtracted from GDP. The Gross National Happiness, GNH, proposed in Bhutan already in the 1970s based on Buddhist ideals suggests that beneficial development of human society takes place when material and spiritual development occur side by side to complement and reinforce each other. The four pillars of GNH are the promotion of sustainable development, preservation and promotion of cultural values, conservation of the natural environment, and establishment of good governance. Both GNH and GPI are based on the assumption that subjective measures like well-being are more relevant and important than more objective measures like consumption.

Many cities have developed programs for social sustainability, then referring to social and democratic reforms often with a focus on public health. There is however no consensus on what constitutes social sustainability (rather what is not included). You may say it is an attempt to develop a life pattern based on quality rather than quantity. An interesting initiative is the Cittàslow movement. Città is Italian for cities and Cittàslow refers to “slow cities.” Here the efficient fast life style is abandoned for a slower more quality-based pattern, e.g. in food (local food, not global fast food) or traffic patterns, and pursuing the unique qualities of the city. The slow cities movement exist in several countries.

Many cities have developed programs for social sustainability, then referring to social and democratic reforms often with a focus on public health. There is however no consensus on what constitutes social sustainability (rather what is not included). You may say it is an attempt to develop a life pattern based on quality rather than quantity. An interesting initiative is the Cittàslow movement. Città is Italian for cities and Cittàslow refers to “slow cities.” Here the efficient fast life style is abandoned for a slower more quality-based pattern, e.g. in food (local food, not global fast food) or traffic patterns, and pursuing the unique qualities of the city. The slow cities movement exist in several countries.

The European value studies (now expanded to world value studies) is a research programme since many years repeatedly investigating the values (ethics) of different cultures and countries. The most important values are quite different in different societies. Very interesting is the analysis of so-called social capital in the countries. Social capital is understood as the trust inhabitants have in each other. It is uniquely high in the Nordic countries, while much less for Eastern and Central Europe, where trust most typically is in the family rather than in society at large. Social capital has been seen as a crucial part of social sustainability.

On the highest level in the Maslowian stairs are the spiritual needs of the individual. Spirituality has a role in a sustainable lifestyle. As we have seen transition to a sustainable society will mean a less materialistic lifestyle, a slower life pace and more time with family and friends. It will also give more importance to the connection with Nature. A sustainable society also underlines the responsibility we all have for our common planet Mother Earth and all life forms. These values may be best expressed in the Earth Charter. The spiritual realm refer to ethics and values (See Chapter 1d) and since the sustainability concept is a normative concept, it is natural to see the spiritual dimension of a society developing with sustainability.

On the highest level in the Maslowian stairs are the spiritual needs of the individual. Spirituality has a role in a sustainable lifestyle. As we have seen transition to a sustainable society will mean a less materialistic lifestyle, a slower life pace and more time with family and friends. It will also give more importance to the connection with Nature. A sustainable society also underlines the responsibility we all have for our common planet Mother Earth and all life forms. These values may be best expressed in the Earth Charter. The spiritual realm refer to ethics and values (See Chapter 1d) and since the sustainability concept is a normative concept, it is natural to see the spiritual dimension of a society developing with sustainability.

Materials for session 8c

Basic level

- One Planet Living by WWF

- Your personal environmental management. Power Point by Lars Rydén, 2010

- Read the Sustainable lifestyle report by Stockholm Environment Institute, SEI

- Read the WWF Pocket Guide to a One Planet Lifestyle (pdf-file)

- The Five Levels of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs by Kendra Cherry

- Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs by Huitt, Valdosta State University (2007).

Medium level (widening)

- Read the Overview in the Human Development Report 2011 - Sustainability and Equity: A Better Future for All by UNDP. p. 1-12.

- Listen to: Costing Not Less Than Everything: sustainability and spirituality in challenging times by Pam Lunn. The Swarthmore Lecture 2011.

- Quality-of-life research at Sustainable Europe Research Institute, SERI

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 12: Social Capital and Traditional-Conservative Values in the Baltic Region.

- Study the List of Countries by Distribution of Wealth

Advanced level (deepening)

- Study the Woodbrooke Good Lives Project. A Quaker community working on the social, community, psychological and spiritual dimensions of climate change, peak oil, and sustainability.

- Study the Cittaslow cities and Transition Towns movement from the point of view of social sustainability.

- Study the Human Development Report 2016 - Human Development for Everyone by UNDP.

- Compare the different ways to measure progress and welfare:

Gross Domestic Product, GDP;

Genuine Progress Indicator, GPI;

Gross National Happiness, GNH;

Human Development Index, HDI and;

Weighted Index of Social Progress, WISP. - The Bill by Germanwatch (YouTube film)

References

Gonçalves, E. 2008. The WWF Pocket Guide to a one Planet Lifestyle. WWF International. Gland, Switzerland.

Maciejewski, W. (ed.) 2002. The Baltic Sea Region – Cultures, Politics, Societies. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

UNDP. 2011. Human Development Report 2011 - Sustainability and Equity: A Better Future for All. United Nations Development Programme, New York, USA.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

9a.

Governance and democracy

How should a society be organised politically to approach sustainability? The basic document, which addresses this question, is the Agenda 21 from the 1992 Rio UNCED Conference. Here the importance of democracy with participation and involvement of all stakeholders in a society is underlined. Participatory democracy is thus seen as the political system under which it is possible to approach and govern a sustainable society. Democracy is also the system, which more than other systems guarantee the human values described in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. There are good reasons to choose democracy. Historical experience shows that strongly centralised authoritarian systems sooner or later disregard environmental protection, good resources management and human rights to protect its own power. Examples of such mismanagement are to be found both in history and in present regimes all around the world.

Democracy as a social invention has a long history but modern democracies did not exist until about 100 years ago. Since then, with setbacks under the first and second World Wars, as well as in connection with the decolonisation in the 1960s and early 70s, democracy has been introduced in a growing number of states. Today more than half of the world population live in formal democracies with universal suffrage. Difficulties when going from an authoritarian system to democracy includes that the citizens should take responsibility, even if there is no such tradition and many rather want a “strong leader” to take care of them. On the way to democracy to reduce corruption is typically a slow and difficult process, while free media is often in the forefront.

For sustainability democracy design is crucial. The traditional representative democracy, limited to voting, has not been able to respond to all demands of sustainable development. It lacked the elements of participation, listening, mutual understanding and changing views in the political process, which is present in participatory or, more often, deliberative democracy. This on the other hand characterises governance. Governance asks for less bureaucracy and an increased distribution of responsibilities of realisation, economy and maintenance in societal issues; it is more entrepreneurial, stresses competition, markets and customers, and measures outcomes. This transformation of the public sector, the authorities, may be summarised as less government but more governance.

For sustainability democracy design is crucial. The traditional representative democracy, limited to voting, has not been able to respond to all demands of sustainable development. It lacked the elements of participation, listening, mutual understanding and changing views in the political process, which is present in participatory or, more often, deliberative democracy. This on the other hand characterises governance. Governance asks for less bureaucracy and an increased distribution of responsibilities of realisation, economy and maintenance in societal issues; it is more entrepreneurial, stresses competition, markets and customers, and measures outcomes. This transformation of the public sector, the authorities, may be summarised as less government but more governance.

The authorities build institutions for the purpose of implementing their policies. Some see institutional sustainability as the equally important as environmental, social and ecological sustainability. Institutions have the task of implementing, monitoring, reporting and regulating society according to the tasks given to them by the governing decision-makers. A task of special concern for sustainable development includes monitoring, e.g. emissions of greenhouse gases, presence of chemical pollutants, development in the field of energy etc. to give decision-makers the needed background; still this monitoring and reporting is much weaker than in e.g. the financial sector.

Democracies vary in distribution of power between the local and central levels. Sustainability politics typically stresses the role of the local level, and has Local Agenda 21 as the basic document. To be successful the local level needs three competences: legal, economic and expertise. The local level should thus have enough power to regulate on the local level, exemplified by the planning monopoly, enough economic strength to execute necessary reforms, which requires a strong local taxation, and finally the expertise needed to monitor and plan for a sustainable future. City networks such as the European Sustainable Cities and Towns Campaign asks for a strong local level development and the role of good governance, illustrated by the Aalborg commitments (See further Chapter 4a).

Democracies vary in distribution of power between the local and central levels. Sustainability politics typically stresses the role of the local level, and has Local Agenda 21 as the basic document. To be successful the local level needs three competences: legal, economic and expertise. The local level should thus have enough power to regulate on the local level, exemplified by the planning monopoly, enough economic strength to execute necessary reforms, which requires a strong local taxation, and finally the expertise needed to monitor and plan for a sustainable future. City networks such as the European Sustainable Cities and Towns Campaign asks for a strong local level development and the role of good governance, illustrated by the Aalborg commitments (See further Chapter 4a).

Democratic government and implementation of the principles of democracy has been monitored in various ways. A most interesting and relevant report is published by the World Justice Project, WJP, as an “effort to strengthen the rule of law for the development of communities of opportunity and equity”. The rule of law includes four principles: that government and its officials are accountable under the law; that the laws are clear, publicized, stable and fair; that the process by which the laws are enforced is accessible, fair and efficient; and that access to justice is provided by competent, independent, and ethical adjudicators.

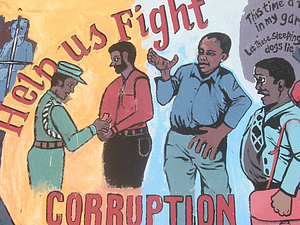

The Word Justice Project index monitors the rule of law in nine segments: Limited government powers; Absence of corruption; Order and security; Fundamental rights; Open government; Effective regulatory enforcement; Access to civil justice; Effective criminal justice: and Informal justice. In 2011 a total of 66 countries had been assessed and reported for. Other important monitoring bodies include Transparency International, which measures corruption in the world since more than 20 years. Corruption is in many ways an equally serious threat to the development of a country as lack of democratic institutions or even climate change, as resources intended for development is used to build private fortunes.

The Word Justice Project index monitors the rule of law in nine segments: Limited government powers; Absence of corruption; Order and security; Fundamental rights; Open government; Effective regulatory enforcement; Access to civil justice; Effective criminal justice: and Informal justice. In 2011 a total of 66 countries had been assessed and reported for. Other important monitoring bodies include Transparency International, which measures corruption in the world since more than 20 years. Corruption is in many ways an equally serious threat to the development of a country as lack of democratic institutions or even climate change, as resources intended for development is used to build private fortunes.

The right to free exchange of ideas, to assemble and to organize is essential for the democratic process. Civil society refers to all individuals and organizations in a country that is not state or authority. Civil society organizations are referred to as Non-Governmental Organizations, NGOs. Many people see the topics of sustainable development, protection of nature, and the fight against climate change, as existential questions. Here the right to organize to influence political as well as other processes in society is essential. Such organizations play a very important role in the changes we see. The possibilities to influence have increased tremendously with the access to new information technologies.

Business, which may be included in civil society or seen as a separate sector, has a key role. In a modern, western state this the private sector accounts for some 85% of the economy. From companies and employees taxes are paid to the authorities on national, regional and local levels, to make it possible for them to execute the policies agreed on in the country. Since the 1970s Western Europe, and since 1990s Central and Eastern Europe, have undergone large-scale privatizations with enormous assets originally owned by the state transferred to the private sector, e.g. trains, mines, electricity, telephone and communications. More recently we also see social services become privatized, such as healthcare, schools, elderly care etc. This means that the attitudes and projects for sustainable development in the business sector are of key importance.

As a result national, regional and local authorities increasingly do not have enough political and financial power for planning and implementing plans. To plan for future changes and to be able to implement the plans, actors and stakeholders enter into different types of coalitions, public private partnerships (PPP). These include a mix of public and private actors, each capable of bargaining on their own behalf; partners are expected to bring something to the partnership, and share responsibility for the outcomes of their activities. Disadvantages include an unclear relation of responsibility between the population and their political representatives, and an increased risk of corruption.

Another key actor in the changes a society undergoes is science. Research at universities, academy institutions, and research institutes develop our knowledge and understanding of the world. Research financers, among them the state, largely select research priorities; during the last decade sustainability research have been well financed. The research results should be under constant discussion and criticism, and controversial results should at best provoke other scientists to try to replicate, falsify or confirm. This is part of a sound scientific process. But it appears that when science results are uncomfortable enough some politicians do not want to face the consequence, they rather attack the science on which they are built, which appears to explain some climate denial.

Another key actor in the changes a society undergoes is science. Research at universities, academy institutions, and research institutes develop our knowledge and understanding of the world. Research financers, among them the state, largely select research priorities; during the last decade sustainability research have been well financed. The research results should be under constant discussion and criticism, and controversial results should at best provoke other scientists to try to replicate, falsify or confirm. This is part of a sound scientific process. But it appears that when science results are uncomfortable enough some politicians do not want to face the consequence, they rather attack the science on which they are built, which appears to explain some climate denial.

In a living democracy it is far from enough to express your view when voting each four or so years. Media like TV, radio, and newspapers, sometimes described as the third power in a state (the other being government and the court system) has a key role in a living democracy. It allows for an ongoing public debate, proposals and arguments, as well as distributing the result of science and research. In the best case the media serves to educate the population on a daily basis, which is a key question for sustainable development. Where democratic institutions are defeated media is usually the first victim, as power holders want to control all information distributed in the country, another illustration of the connection between democracy and sustainable development.

Materials for session 9a

Basic level

- Study Environmental Science, chapter 22, especially pp 665-684: Making and Implementing Environmental Policy.

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 19, pages 285-289: The Historical Breakthrough of Democracy.

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 21, pages 296-299: Territorial Power Distribution.

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 22, pages 300-307: The Civil Society: Parties and Associations.

- Read Baltic Sea Region, chapter 25, pages 333-343: Malfeasance in Contemporary Democratic Societies.

- An Agenda for Global Responsibility The Finnish Ministry of Education and the Baltic Univeristy Programme, 2008.

Medium level (widening)

- Study the World Justice Project in Constructing the WJP Rule of Law Index, p 7-17.

- What is Good Governance? By United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Pacific, ESCAP.

- Read on Non-governmental Organizations in Global Issues.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Study the role of Public-Private Partnership (PPP) in the Handbook of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) for their role in SD, e.g. infrastructure development.

- Study the role of NGOs in The Rise and Role of NGOs in Sustainable Development from International Institute for Sustainable Development, IISD.

Additional Material

Vladlena Gladchenko and Marie Thynell: The Political Dimensions of Sustainability .

References

Maciejewski, W. (ed.). 2002. The Baltic Sea Region – Cultures, Politics, Societies. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

Rydén, L., Migula, P. and M. Andersson (eds.). 2003. Environmental Science - understanding, protecting and managing the environment in the Baltic Sea region. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

9b.

International cooperation and world order

No country can achieve sustainability on its own. International cooperation has therefore become a necessary feature and is developed on a number of levels and on different scales. On the global level the United Nations and all its organisations are the most important. In Europe the European Union is the most important, and there are similar organisations in other parts of the world, mostly focusing on economic matters, as well as cooperation between smaller groups of countries including the countries around the Baltic Sea. Finally among NOGs there is a vivid international networking taking place, and many of the most important organisations for promoting sustainable development are international.

The United Nations was created in 1945 to safeguard and build peace in the world, but very soon it took on a much wider spectrum of resposibilities. UNESCO, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization was formed in 1945; IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources today called the World Conservation Union, was formed in 1948; and UNDP, the United Nations Development Programme was formed in 1965 and UNEP, the Environmental Programme in 1972. A number of special organisations are part of the UN family, such as the World Health Organisation, WHO, and World Meteorological Organisation, WMO. All of these have major roles in UN’s work for Sustainable Development. UNESCO has a main responsibility for the decade for Education for Sustainable development, ESD; IUCN is mainly responsible for the work to protect biodiversity, and UNEP for the environmental work.

Before and after the groundbreaking UNCED conference in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, the UN work for sustainable development took new ground. The CSD, Commission for Sustainable Development, coordinated at the UN headquarter in New York, got the task to follow up the work started and agreements reached at the Rio Conference, especially the Agenda 21.

International cooperation takes the form of global conventions, agreements between governments on specific topics. Three of them, the Rio conventions, were created in connection with the Rio conference: the Framework Convention on Climate Change UNFCCC, the Convention on Biological Diversity, CBD, and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, UNCCD. Long before that several other global agreements had been created and implemented; among the earliest, from 1958, are the conventions to protect international waters, including the convention on protection of fishing and fishing resources.

International negotiations have limitations. The UN system mostly relies on consensus, but the present 194 member states very seldom agree completely. This is illustrated by the climate negotiations, which has been unsuccessful, as there is no global agreement on limitation of emissions of GHGs, despite efforts since the Climate Convention was created 20 years ago. Similarly the other Rio Conventions have very few binding obligations for the parties. There is thus very little of a global legal structure with agreements, monitoring, reporting and sanctions for states, which break a decided agreement. It is quite different from the European Union, where such agreements are the norm. We rather have a system where states proceed according to an international agenda as they deem it is in their own interest to do so.

The United Nations constitutes a crucial meeting arena for all countries in the world, also those, which are in deep conflict. The UN organisations continuously organize smaller and larger meetings of all kinds, especially on peace and conflict issues, on economic development etc. and all member states meet yearly in the UN General Assembly. Among the ground-breaking conferences on the global level we should mention the largest so far, the 1992 UNCED conference, the 2002 Johannesburg World Summit on Sustainable Development and the Rio+20 conference in 2012. Of special relevance for sustainable development are the two conferences on Human Settlements, called Habitat from 1976 and 1996 and four world conferences on women, the latest in Beijing in 1995.

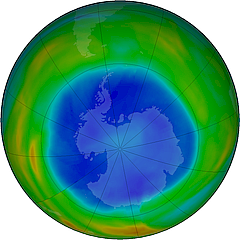

Many conventions are more specialised and on a lower level. Still the United Nations plays a main role in their management and implementation. These include two very successful conventions on air pollution. The Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollutants from 1979, is a convention in the UN Economic Commission for Europe, while the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer and its Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, from 1987 was initiated between 20 countries, later expanded and then managed by a Fund of three UN bodies, including UNEP, and the World Bank.

Many conventions are more specialised and on a lower level. Still the United Nations plays a main role in their management and implementation. These include two very successful conventions on air pollution. The Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollutants from 1979, is a convention in the UN Economic Commission for Europe, while the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer and its Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, from 1987 was initiated between 20 countries, later expanded and then managed by a Fund of three UN bodies, including UNEP, and the World Bank.

The main concern for the United Nations is to safeguard peace. In this regard international cooperation has been successful. Today there are no classical interstate wars in the world. The number of armed conflicts - typically about state power or the definition of the state - are still large but since some years slowly decreasing. Skilled negotiators contribute to conflict resolution and the number of interstate peace agreements is increasing. The economic development of the world contributes. Economic cooperation is increasingly a better option than conflict, and economic alliances, such as the EU, constitute security communities, where conflicts do not escalate to armed confrontations. But most important is increased democracy. Democracies do not enter into armed conflict with each other. In a sustainable world war will be found only in the history books. Of future international security threats most often mentioned are the climate threats such as extreme weather events, heat waves and failed harvests. If future competition on key resources, such as oil and other energy resources, or an increasing number of climate refugees, will lead to new wars, remains open.

Many argue that the world is in such a danger that we need a global government, a global legal order. The United Nations is not that. On the contrary the Security Council, which is a key body in the UN system, is limited by the willingness of several major powers not to use their veto to stop a proposal. Proposed reform of the UN system has not been executed. Some see this with regret and even despair. Others argue that compared to the situation just some decades ago progress has been enormous. After all, there are a number of global organisations which do an enormous work to improve the situation in many countries. There are a number of agreements, which have been reached, successfully implemented and which are efficient.

On the European level the European Union has played a main role. It started as a cooperation between six states on coal and steel in the 1950s. Today it is the most developed international cooperation in the world, with 27 member states and 3 more participating in legal and economic matters. The European Union was originally a peace project after hundreds of years of conflict in Europe, and based on economic cooperation EU soon became of key importance for environmental protection and sustainable development. The Union adopted its first environmental laws in the 1970s. A more serious environmental policy started with the 3rd Environmental Action Programme in 1983. Since then EU environmental and sustainability policies have developed rapidly and a strategy for Sustainable Development was adopted in 2001. Today the EU has an extensive body of environmental directives and regulations many of which are of key importance for sustainable development work in the Union.

In the Baltic Sea region development of cooperation has been strong and early. The negotiations for a convention on the protection of the Baltic Sea started immediately after the Stockholm conference in 1972. It was signed in 1974 and ratified by all parliaments in 1980. A much updated and expanded convention text was signed in 1992. The Council of the Baltic Sea States, CBSS, with 12 member countries was formed by the foreign ministers in the region in 1992. In 1996 prime ministers from all the countries met in Visby on Gotland to sign an Agenda 21 for the Baltic Sea region, the first regional Agenda 21 in the world, called Baltic 21. It is today part of the CBSS. These Intergovernmental organisations, IGOs, are only the most important of a long series of cooperative structures which include local authorities in Union of Baltic Cities, a long series of NGOs, such as WWF, and financers of sustainable development work on national and EU levels.

In the Baltic Sea region development of cooperation has been strong and early. The negotiations for a convention on the protection of the Baltic Sea started immediately after the Stockholm conference in 1972. It was signed in 1974 and ratified by all parliaments in 1980. A much updated and expanded convention text was signed in 1992. The Council of the Baltic Sea States, CBSS, with 12 member countries was formed by the foreign ministers in the region in 1992. In 1996 prime ministers from all the countries met in Visby on Gotland to sign an Agenda 21 for the Baltic Sea region, the first regional Agenda 21 in the world, called Baltic 21. It is today part of the CBSS. These Intergovernmental organisations, IGOs, are only the most important of a long series of cooperative structures which include local authorities in Union of Baltic Cities, a long series of NGOs, such as WWF, and financers of sustainable development work on national and EU levels.

Materials for session 9b

Basic level

- Study international cooperation in Environmental Science, chapter 23, especially pages 693-702: International Cooperation for the Environment.

- Study Environmental Science, chapter 23, especially pages 702-705: International Cooperation for the Environment.

- Read Environmental Management, book 1, chapter 2, pages 39-52: The Development of the European Union Environmental Regulation.

- Read The Baltic Sea Region, chapter 22, pages 300-307: The Civil Society: Parties and Associations.

- Read The Baltic Sea Region, chapter 25, pages 333-343: Malfeasance in Contemporary Democratic Societies.

Medium level (widening)

- Study the European Union environmental cooperation in Environmental Science, chapter 23, especially pages 706-717: International Cooperation for the Environment.

- Study the Baltic Sea region environmental cooperation in Environmental Science, chapter 23, especially pages 718-726: International Cooperation for the Environment.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Study the European Union policy for Sustainable Development.

- Study the management of the Global Conventions: Signing, Ratification, Entry into force, Convention secretariats, Protocols and Conferences of the Parties, COPs. Begin with Environmental Science, chapter 23, especially pages 697-702: International Cooperation for the Environment and then look at the home page of a convention of your choice.

References

Klemmensen, B., Pedersen, S., Dirckinck-Holmfeld, K. R., Marklund, A. and L. Rydén. 2007. Environmental Policy - Legal and Economic Instruments. Environmental Management Book 1. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

Maciejewski, W. (ed.). 2002. The Baltic Sea Region – Cultures, Politics, Societies. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

Rydén, L., Migula, P. and M. Andersson (eds.). 2003. Environmental Science - understanding, protecting and managing the environment in the Baltic Sea region. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

9c.

Making and implementing sustainable development politics

Social problems do not appear on the political agenda until they are perceived as social problems by the policymakers. Actors who want changes in society have to introduce their concerns on the agenda. Sustainable development was introduced as a political concern after the raising environmental movement in the 1960s, followed by the Stockholm conference in 1972 and finally the Brundtland Committee Report Our Common Future in 1987. After the Rio UNCED conference, it was established on the agenda all over the world.

Social problems do not appear on the political agenda until they are perceived as social problems by the policymakers. Actors who want changes in society have to introduce their concerns on the agenda. Sustainable development was introduced as a political concern after the raising environmental movement in the 1960s, followed by the Stockholm conference in 1972 and finally the Brundtland Committee Report Our Common Future in 1987. After the Rio UNCED conference, it was established on the agenda all over the world.

Many factors influence politicians when they make political decisions. These include their ideology on how to develop their country. There are pressure groups, which do their best to influence the politicians, and there are also business interests, budget limitations, and not the least concern about the voters. Politics that will severely decrease the odds to be re-elected have small chances. One may argue that it is not the politicians, which lead the development of society – the voters have to be ahead. Politics leading towards a transition to a sustainable society will, according to this view, start from below.

Politics is implemented as governments, parliaments and local authorities decide on new laws and regulations and economic measures such as taxes or subsidies (which are a kind of regulations). The decisions are implemented by authorities, among them Environmental Protection Agencies, Energy Agencies etc, which are given the administrative, financial and legal resources needed. Authorities work though information, legal regulations and economic subsidies or taxation. The implementation of politics is monitored by the authorities and in the final stage, if it is not followed, the police and court system will deal with this.

Different political parties and interest groups choose different strategies for sustainable development. Neoliberal groups argue for business as usual and that the market forces will take care of it, e.g. the price of oil will increase as oil becomes scarce, and then renewable energy will be competitive. Others argue that human ingenuity always solved problems when confronted with the necessity to do so. This technological optimism leaves the problem to the engineers. Those promoting green business as the solution argue for ecological modernization as the answer to the sustainability challenge. Another group asks for responsible policies and respect for ethics and values. All experience shows that none of these strategies will lead to sustainable development by themselves, but that all of them will contribute to an extent. One may see sustainable development as a strategy in itself with its own methods (See further Session 11a) or subdivide the main types of strategies mentioned above into detailed measures.

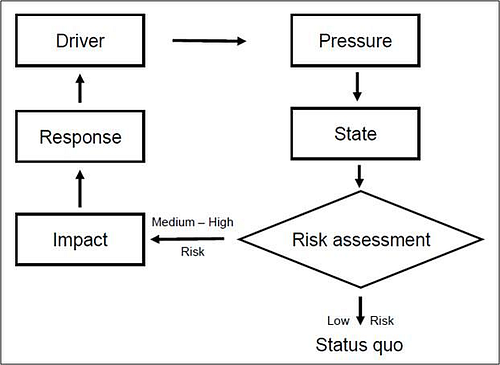

The European Environment Agency uses a formalized description of the process in which an environmental problem appears and enters the political agenda, a process that may be generalized for the more general sustainability issues. The process is known as the Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) framework. Driver is the activity which leads to an impact, such as an industrial process; Pressure is the consequence of that activity such as a pollutant released into water or air; State is the condition it leads to e.g. an increased concentration of a pollutant in the environment: Impact is the consequence for example sick people or disappearance of a species; Response is what the authorities do to improve the state of the environment or society. This sequence of events should be followed by an evaluation and possibly planning for a new round of steps.

In a study on the success of sustainable development work in European cities, it was clear that the most successful local authorities had implemented clear work strategies. First, it was crucial that the head of the city administration as well as the politicians were concerned about sustainable development, so the whole organization had a strong support from the leadership. Secondly, there was more integration between the different departments of the city administration not only in the environmental side but also between economic and planning departments, that is, they used integrated sustainability management. Thirdly, the successful cities more than the others had an active policy for learning, that is, they had implemented institutional learning, as a crucial work strategy. This requires coordination and planning; it is not enough that a few specialists are aware of the background and reason for work.

Materials for session 9c

Basic level

- Study policymaking in Environmental Science, chapter 22, especially pages 665-669: Making and Implementing Environmental Policy,

- Study the policy-makers in Environmental Science, chapter 22, especially pages 670-675: Making and Implementing Environmental Policy,

- Study implementation of policies in Environmental Science, chapter 22, especially pages 676-687: Making and Implementing Environmental Policy.

Medium level (widening)

- Study sustainable development strategies in National Strategies for Sustainable Development: Challenges, Approaches and Innovations in Strategic and Coordinated Action by International Institute for Sustainable Development, pp. 1-44.

- Study the DPSIR framework for working with impacts on society. For example, at this link.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Study institutional learning in Organisational and Institutional Learning in the Humanitarian Sector from ALNAP, Active Learning Network

References

Rydén, L., Migula, P. and M. Andersson (eds.). 2003. Environmental Science – understanding, protecting and managing the environment in the Baltic Sea region. Baltic University Press, Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

Sida 10 av 15