Välkommen till Svenska Aralsjösällskapet

10a.

Economy and ecology – a single system

Economy is regularly defined as one of the (three) pillars, or dimensions, of sustainable development - Environmental, Social and Economic - all of which need to work to achieve a sustainable society. While environmental concerns have dominated the discussion for a long time we now see a change. Increasingly the language of sustainability comes closer to that spoken by politicians and businessmen. People start to realize that environmental issues need to be seen in a much broader perspective than before. They are not just a matter of environmental protection, but also a matter of long-term economic strategies. Below we will illustrate how economy is connected to environmental development but also how it influences the social situation of a country.

Economy is regularly defined as one of the (three) pillars, or dimensions, of sustainable development - Environmental, Social and Economic - all of which need to work to achieve a sustainable society. While environmental concerns have dominated the discussion for a long time we now see a change. Increasingly the language of sustainability comes closer to that spoken by politicians and businessmen. People start to realize that environmental issues need to be seen in a much broader perspective than before. They are not just a matter of environmental protection, but also a matter of long-term economic strategies. Below we will illustrate how economy is connected to environmental development but also how it influences the social situation of a country.

The science of ecological economics attempts to study economy, the environment and natural resources together. It is obvious that economy depends on natural resources and those in turn depends on how the economy - e.g. forestry or agriculture or industrial production, which may lead to pollution - is conducted. Society, economy and nature together form a single system, in which all components influence each other.

Many environmental goods are traded on a market just as any other goods. Timber, agricultural products, mined metals and fossil resources are traded and have prices, and are thus part of the normal economy. When this trade have negative effects, which are not paid for - it may be both environmental and social negative effects - these are called externalities. Typical externalities include pollution by factories, roads that intrude in the landscape, and carbon dioxide emissions from transport e.g. air traffic. Pollution may decrease the health of the people leading to higher medical costs, or reduce the production of nature and thus lower the income from forests, fields and the sea.

When the price of a product does not represent its true costs we have a market failure. Market economy does not automatically take care of the environmental costs of the economy. In fact it never does as “free” ecosystems services are supporting all activities in the system Nature-Economy. The value of all ecosystems services on Earth has been estimated and the result is much larger than the value of the total economy, that is, the world Gross Domestic Product, GDP.

One way to deal with this is that the State introduces an environmental tax. In this way an externality may be included or even avoided, for example when a factory finds it economically better to develop a production without pollution. The State may also use the tax money to restore the environment, for example when a tax on e.g. emissions of air pollutants such as SOx is used for the liming of acidified lakes.

An environmental tax that makes the polluter pay at least some of the cost of polluting, is fulfilling the so-called Polluters Pay Principle, meaning that those who pollute should pay for the damage caused, most typically for the cost of remediation. In real life it is often difficult or impossible to find the polluter, e.g. when a country is hit by acid rain. Instead too often it is the victim who pays. Today we are fighting to remedy quite much of the consequences of earlier environmental sins, e.g. by remediation of brown fields. Those are much polluted earlier industrial areas, which are often extremely expensive to clean up. This is the environmental debt of earlier generations.

An environmental tax that makes the polluter pay at least some of the cost of polluting, is fulfilling the so-called Polluters Pay Principle, meaning that those who pollute should pay for the damage caused, most typically for the cost of remediation. In real life it is often difficult or impossible to find the polluter, e.g. when a country is hit by acid rain. Instead too often it is the victim who pays. Today we are fighting to remedy quite much of the consequences of earlier environmental sins, e.g. by remediation of brown fields. Those are much polluted earlier industrial areas, which are often extremely expensive to clean up. This is the environmental debt of earlier generations.

But what about environmental goods and services which are never sold and bought on a market? Can they be given a price? Sometimes a price can be calculated as an indirect cost. Thus the prices of all properties at the shore of a sea before and after it has been polluted reflects the price of a clean sea. In absence of a market price one may simply ask people what they are willing to pay (willingness to pay, WTP method), for example for the possibility to pick mushrooms in the forest, or to be able to swim in a nearby lake.

There are also services, which do not have a price, that are priceless, such as the beauty of a mountain range or the existence of the biodiversity of a coral reef, they have existence value. It is also obvious that monetary methods have limits. We have to preserve the basis for our lives regardless of what the market says. “When the last tree is cut, the last fish is eaten, it will be obvious that we cannot eat money.”

When asking who owns the environment, the answer above is “the state”, as the state is able to collect environmental tax. Sometimes this does not apply. The World’s Oceans for example do not have an owner in this sense. Therefore fishing fleets may harvest as much fish as they can, not to let someone else do it. As a consequence the resource is partly or completely destroyed, a reality of today’s ocean fishing. This is called the tragedy of the commons. An unregulated common resource is at danger. We see national states regulating their common resources, and some international regulations, e.g. fishing within the European Union waters, but the so called global commons – Antarctica, the oceans, the atmosphere - are in danger. Global warming can be seen as the failure to regulate the use of the atmosphere as a recipient for greenhouse gases.

The environment is thus valuable, but where is the wealth of nations? The collected value of all goods and services sold and bought in a nation is traditionally expressed as Gross National Product, GNP. The weakness is that it includes transactions, which are not understood as wealth, such as health services, and excludes others, which are percieved as wealth, such as natural resources. These are included in a green GNP and green budgets. The absolute value of a green GNP is not possible to establish. The large value of working with a green budget or green GNP is rather to follow the changes from one year to the next. Green budgets include traditional statistics (production values, processing value, employment), but also adds positive items (energy as biomass etc, and natural resources such as forests, fisheries etc) and subtract negative ones, such as emissions. The World Bank, which in this way has reported on the wealth of nations, emphasise the importance of agriculture, especially in the developing world.

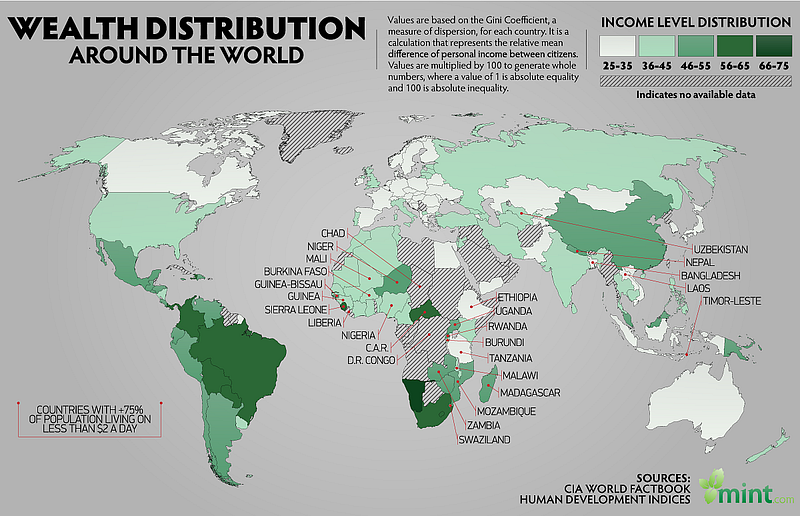

But equally important as the wealth of nations is the distribution of wealth. The economic inequity between, as well as within, countries has typically increased since the 1970s. Large income inequalities are by many considered a problem as serious as the environmental crisis. A country with large personal income inequalities has larger problems in medical and psychological health, crime, gender equity, social trust etc. In Europe a key task for the welfare state is to function as a huge re-distributor of income to reduce inequity by collecting taxes and supporting those without income. (See further Chapter 10c).

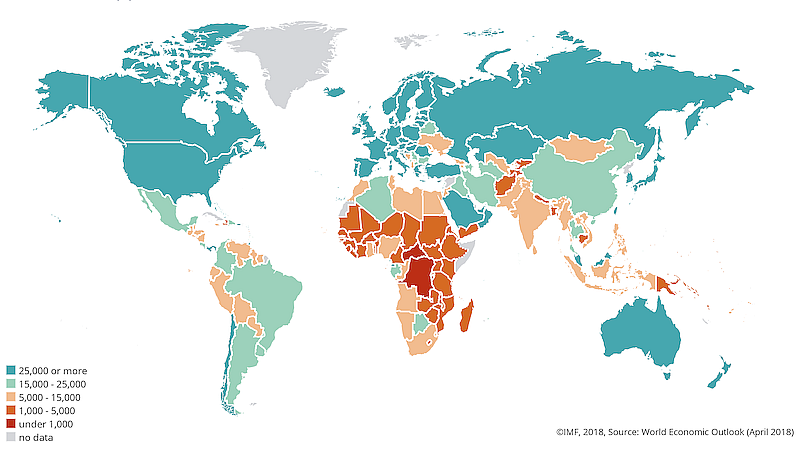

We see that many countries, especially in Asia, which a generation back was considered developing or underdeveloped, are today counted as middle-income states. Especially in Asia the economic development has been dramatic. Still there are a number of countries, most of them in Africa, with enormous poverty. The redistribution of economic means to these through e.g. loans, development support etc., is minimal compared to for example international trade or military budgets. The United Nations asked the countries of the world to address this question in the Millennium Development Goals adopted by the General Assembly in year 2000 to be reached by 2015. Reducing poverty is one of the goals; it will be met by the target year. It will help to meet a number of other key development goals both social (child survival, education, population growth) and environmental (food production, resource use and environmental impact).

One finally needs to reflect on the meaning of economy. Money is there not for its own sake, but rather as a mean to achieve welfare and a good life. Is there enough for us to share (equity within the existing generation) and save for the coming generations (equity between generations)?

Materials for session 10a

Basic level

- Study Environmental Science, chapter 19, pages 569 - 574: Basics of Ecological Economics.

- Study Environmental Science, chapter 19, pages 574 - 579: Cost of Environmental Impact and Green Budgets.

- Study Environmental Science, chapter 19, pages 583 - 589: Environmental Taxes.

Medium level (widening)

- Study how to perform Green Accounting, by Geir B. Asheim.

- Learn about different measure of economic standard (e.g. GDP/Capita), wealth distribution (Gini coefficient or quintiles)

- Read about the book The Spirit Level on social consequence of unequal distribution of wealth

- Study distribution of wealth in your own country.

- Watch the presentation by Elinor Ostrom on Tragedy of the Commons.

- Read Raymond De Young’s Tragedy of the Commons, Adaptive Muddling and Durable Behaviour: Bringing out the best in people faced with difficult environmental circumstances.

- Hans Rosling: New insights on poverty.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Read Environmental Science, chapter 19, pages 569 - 589: The Cost of Pollution - Environmental Economics.

- Study The Sustainable Development Goals; Find out what they are and how far they are from being reached. On the UNDP web site (first). On the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) homepage (second).

- Study the World Bank report Where is the Wealth of Nations. Find out how it is calculated and look up your own country in the tables in the back.

- Read Chapters 9 and 10, pages 1- 47 in: Branko Milanovic (2005), Worlds Apart: Measuring Global and International Inequality.

References

Milanovic, B. 2005. Worlds Apart: Measuring International and Global Inequality. Princetone University Press.

Rydén, L., Migula, P. and M. Andersson (eds). 2003. Environmental Science - understanding, protecting and managing the environment in the Baltic Sea region. Baltic University Press. Uppsala, Sweden.

Wilkinson, R. G. and Pickett, K. 2009. The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. Allen Lane.

World Bank. 2005. Where Is the Wealth of Nations? Measuring Capital for the XXI Century. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Zylicz, T. (ed.). 1977. A Sustainable Baltic Region. Session 8, pp. 23-29. Baltic University Press. Uppsala, Sweden.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

10b.

The dilemma of economic growth

We live in a society in which economic growth has become a mantra for all policymakers and business people. Even if the overwhelming focus on growth is only some 30 years, the history of economic growth is long. Only during the 20th century, global GNP increased 16 times, see Chapter 1a. Among the several factors behind growth, energy stands out as the most important. The access to cheap fossil fuel is closely linked to economic growth during over a long period. Easy access to energy made labour productivity rise by some 3-4 % yearly over more than a century. A person equipped with a machine can do much more than when just using muscle power!

But where does a never ending economic growth take us? Suppose that all inhabitants should have the standard of living typical for Western Europe (or OECD countries). This means another 15 times increase, and by the end of the century after further growth a 40 times bigger economy in the world. Is this possible? Can growth go on forever – still growth is the basis of present modern economy.

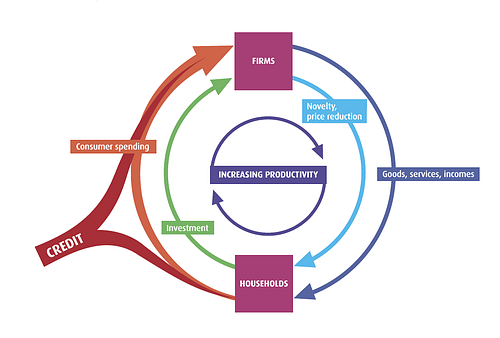

Not surprising when thinking about what happens if there is no growth. Consumption would decrease, companies would not be able to sell their products and would go to bankruptcy, unemployment would mount and so on. The “engine of growth” in market economies allows companies to gain a net profit, which is invested in a development that leads to more growth and jobs. In short, it seems like modern economy has to choose between eternal growth and collapse, both of which are unsustainable. The growth dilemma may be the largest problem for the vision of a sustainable future society.

It is clear that economic growth is crucial up to a point for quality of life, happiness, prosperity, education, health etc. But after that, it appears that economic growth is not so important. In international studies, life expectancy, infant mortality, education, or happiness itself do not increase after a GDP of about 10,000 USD/capita (purchasing power parity using 1995 dollars). In investigations one finds that factors which are important to individual satisfaction and wellbeing do not cost much or cannot be bought at all, such as family, friends, leisure time, enjoying nature etc. Increased income, however, is still a priority in all societies. Why do people rather get richer than happier?

To come to grips with the growth dilemma, we need to ask ourselves which is the role of material possessions. One important aspect is that in society, we tend to judge our prosperity by comparison with others. As long as we are enough equal to our neighbours all is fine, but if they have a better car or even two cars or a nicer house etc. we want the same. Social positioning is the engine of personal ambition and is also fuelling economic growth. It is the social logic behind increased consumption, which the companies need, to develop their businesses, increase profit and – grow!

If economic growth could be unrelated to flows of natural resources, the growth would not be problematic. It could go on forever as long as material consumption does not increase. Increased economy without increasing material flows is called decoupling. Decoupling has been typical for affluent societies, in the sense that economy is growing faster than consumption of resources. The productivity of for example 1 unit of energy (energy intensity) has increased for many years in western societies. But the result of decoupling is offset by an absolute increase in growth, called the rebound effect. We talk about Jevons paradox, meaning that technological progress or efficiency increase, typically leads to increased consumption. We thus have a relative decoupling. On the other hand, absolute decoupling – that the material flow is actually decreasing, while economic growth is increasing – is not seen in our societies.

What kind of solutions do we see for the growth dilemma? One is to dematerialize the economy, that is, an ever-increasing economic value can be given to smaller material things. For example, computers may be quite small and still be very efficient, or that we buy services, for example concerts, much more than material possessions. Much of this has happened. In a modern society, a large proportion of the economy is in the service sector (in Sweden, only about 15% of the workforce is in industry and less than 2% in agriculture and forestry). The efficiency of the production is thus enormous (or relies on imported goods) but it is still offset by increased consumption, and we do not see absolute decoupling.

What kind of solutions do we see for the growth dilemma? One is to dematerialize the economy, that is, an ever-increasing economic value can be given to smaller material things. For example, computers may be quite small and still be very efficient, or that we buy services, for example concerts, much more than material possessions. Much of this has happened. In a modern society, a large proportion of the economy is in the service sector (in Sweden, only about 15% of the workforce is in industry and less than 2% in agriculture and forestry). The efficiency of the production is thus enormous (or relies on imported goods) but it is still offset by increased consumption, and we do not see absolute decoupling.

Another road is green growth. This was a main theme at the 2012 Rio + 20 Conference. Green economy in short only refers to an economy where environmental concerns are taken into account. Here, one component is that material flows become cyclic (recycle all components of products) so that they do not contribute to resource extraction or environmental loads. The economy needs to rely on renewable resources, especially in energy sector. Obviously we need a green sector of the economy, but so far we have not seen it contribute to absolute decoupling. According to the Limits to Growth studies, even very extreme assumptions about technical developments did not in itself solve the problem of limits to growth. They only pushed the peaks further into the future. We have to make lifestyle changes.

As a response to mounting concerns about the growth dilemma, the de-growth movement has developed as a protest against the all-embracing concern with material possessions. The de-growth movement want other ways to measure success. The common practice of using Gross Domestic Product, GDP, as a measure of the success of a country is therefore brought into question. GDP is just the sum of all economic transactions in a country (many of which may be very negative) and was never intended to be a measure of success. The de-growth movement want to focus on welfare, prosperity, or even happiness. See further Chapter 10c.

As a response to mounting concerns about the growth dilemma, the de-growth movement has developed as a protest against the all-embracing concern with material possessions. The de-growth movement want other ways to measure success. The common practice of using Gross Domestic Product, GDP, as a measure of the success of a country is therefore brought into question. GDP is just the sum of all economic transactions in a country (many of which may be very negative) and was never intended to be a measure of success. The de-growth movement want to focus on welfare, prosperity, or even happiness. See further Chapter 10c.

Macroeconomic modelling has been used to explore factors, which might push a capitalist market economy into a steady state, that is non-growth, but still on a high level of prosperity. It turns out that in the common economy, the state or fiscal economy has a large role. Much of the investments are directed to long-term development, such as infrastructure, rather than short-term investments, which are more typical for the private sector. Employment stays on a high level when working hours decrease. No country has tried this recipe, so we do not have practical experience, but the topic is a key point in the British report Prosperity without Growth from 2008.

Materials for session 10b

Basic level

- Read pages 37-46: The Dilemma of Growth in: Prosperity without growth.

- Read pages 29-36: Redefining Prosperity in: Prosperity without growth.

- Read pages 47-58: The Myth of Decoupling in: Prosperity without growth.

Medium level (widening)

- Investigate the character and proposals of the De-growth Movement and science.

- Investigate the possibilities of Green Growth in Chapter 7, pages 67 – 74 Keynesianism and the ‘Green New Deal’ in: Prosperity without growth.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Analyse the possible roads to steady state economy in Macro-economics for Sustainability in: Prosperity without growth, pages 75 – 84.

- Management and politics of a Sustainable Economy in chapters 9 – 11 Flourishing – within limits; Governance for Prosperity; and steps towards a Sustainable Economy, in: Prosperity without growth, pages 85 – 109.

Additional material

Hamilton, J. D. 2012. Oil Prices, Exhaustible Resources, and Economic Growth (from Department of Economics, University of California, San Diego).

References

Jackson, T. 2009. Prosperity without growth: economics for a finite planet. Earthscan.

10c.

Tools for approaching a sustainable economy

How can we turn the growth-economy so that it does not cause resource destruction and environmental damage, but still contributes to the welfare of our societies and inhabitants? There are a number of economic instruments to address this question. Some of these are used by the state, the public sector, and some by the private sector.

Most important is the Ecological tax reform, also called green tax shift. This refers to the transfer of taxation on incomes (salaries) towards taxation of resource flows. The simple logic is that what is scarce has to be used carefully should be taxed, that is natural resources, while what is not limited in this sense, i.e. human work or work opportunities, should not be limited by taxation. This green tax shift has occurred in many countries, but only to a limited extent. Thus, fiscal economy relies on taxation of energy (fossil fuel, e.g. petrol for cars) carbon dioxide emissions, several metals, fertilizers etc, to some extent in several Nordic countries, Germany and the Netherlands. However, to reduce resource flows, a much more drastic reform is needed. This reform is also assumed to reduce unemployment, as taxation of salaries should be drastically reduced.

To distribute taxation and achieve environmental reforms in the most efficient way, countries have used cap-and-trade systems. This means that a number of actors are allowed to emit a specific pollutant up to a cap. To ensure incentives for companies which can lower their pollution emission, rights can be traded between themselves. Such cap-and-trade schemes have been used for different pollutant and different set of actors, especially in the United States. In Europe, the best known case is the EU system for carbon dioxide emissions trading ETS (See Session 2c). The main advantage with cap-and-trade is that emissions can be limited exactly to what the environment is able to handle. However, in reality, the cap is set to what the emitters or economy can afford.

Societies also use positive economic instruments, i.e. subsidies, to support investments promoting sustainable development. Typical subsidies are carbon funds, which are given to support transition to a fossil fuel free economy, such as insulation of houses, green cars, energy efficiency measures, etc. Business are most often reluctant to investing, even when it is profitable, why authorities in different ways try to stimulate the companies. An illustrating case is the project “Energy Efficiency in Large Companies” by the Swedish Energy Authority. 100 large companies took part, all introduced a certified energy management system, they invested a total of 708 MSEK in a total of 1247 projects; tax reductions were only 150 MSEK and annual reduction of energy costs of 400 MSEK, and return of investments thus 1.5 years.

Many states have a strong economic policy to stimulate steps towards a greener business in the private sector. Investing in energy efficiencies, local production of energy and similar steps thus become increasingly profitable with higher prices for fossil energy, trade support better markets etc. Green technologies or green business have become a large sector in the economy of several countries and an important export market. Similarly, we see local authorities greening their cities or towns, both for economic and ethical reasons, and individual households are also in the same manner greening their lives (see further Chapter 5c).

Many states have a strong economic policy to stimulate steps towards a greener business in the private sector. Investing in energy efficiencies, local production of energy and similar steps thus become increasingly profitable with higher prices for fossil energy, trade support better markets etc. Green technologies or green business have become a large sector in the economy of several countries and an important export market. Similarly, we see local authorities greening their cities or towns, both for economic and ethical reasons, and individual households are also in the same manner greening their lives (see further Chapter 5c).

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development has become an important actor in promoting sustainable development in the private sector. WBCSD was formed immediately after the Rio Conference in 1992. It played a significant role during the Johannesburg meeting. WBCSD has stressed the concept of eco-efficiency, which "is achieved by the delivery of competitively priced goods and services that satisfy human needs and bring quality of life, while progressively reducing ecological impacts and resource intensity throughout the life-cycle to a level at least in line with the earth’s carrying capacity."

Companies as well as authorities promote themselves as green or socially responsible in several ways, as it turns out to be good for their business. Environmental reports are often made individually according to the tradition for each company or authority, but in addition there are standards for environmental or sustainability reporting. Best known is the GRI – Global Reporting Initiative – which covers the whole panorama of sustainability, economic, environmental and social, often referred to as the triple bottom line.

Companies as well as authorities may also become certified as environmentally or socially responsible by using an internationally established management standard. The International Organization for Standardization, ISO, has developed several standards and procedures for certification. Most important for sustainability work is the Environmental Management Systems, EMS, standard ISO 14001, and the Corporate Social Responsibility, CSR, which is a guideline ISO 26000, as well as the Energy Management Standard ISO 50001. The introduction of these standards are typical for larger companies, which in turn push their delivering partners further down in the production chain to also introduce such standards.

Companies as well as authorities may also become certified as environmentally or socially responsible by using an internationally established management standard. The International Organization for Standardization, ISO, has developed several standards and procedures for certification. Most important for sustainability work is the Environmental Management Systems, EMS, standard ISO 14001, and the Corporate Social Responsibility, CSR, which is a guideline ISO 26000, as well as the Energy Management Standard ISO 50001. The introduction of these standards are typical for larger companies, which in turn push their delivering partners further down in the production chain to also introduce such standards.

Adoption of management systems, most typically EMS, is part of voluntary business agreements. There are a number of such procedures between the private sector and the authorities. Adoption of such agreements typically eases the implementation of legal requirements and permits and inspections. Regulation and introduction of a number of environmental laws, especially from the European Commission, has played an important role in the improvement of the environmental behaviour of the European private sector.

There are also important financial mechanisms to support a change into a more sustainable economy. The large investors, including pensions funds, bank etc, increasingly choose to use sustainability measures as criteria for investing. The used criteria most often include CSR and GRI. The investors see a company that have a sound environmental profile and a good CSR as a more attractive investment object than one without. The latter may end up in trouble with authorities or the society, as well as their employees where it is working. There are thus very concrete reasons for supporting companies, which may contribute to a transition towards sustainability.

Finally, one should add that the several proposals for how to manage an economy towards steady state (non-growth economy) are part of the toolbox. See Chapter 10b.

Materials for session 10c

Basic level

- Read Environmental Management, book 1, chapter 11, pages 158-159: Sustainable Development and the Concept of an Ecological Tax Reform.

- Read A Sustainable Baltic Region, session 8, chapter 7, pages 43-46: Ecological Tax Reform by Svante Axelsson.

- Read Environmental Management, book 1, chapter 11, pages 149-158: Market-based Economic Instruments – Emission Trading.

- Read Environmental Management, book 1, chapter 4, pages 65-76: Self-regulation and Voluntary Corporate Initiatives

Medium level (widening)

- Study the role of European Union regulations in Environmental Management, Book 1, Chapter 2: Development of EU Environmental Regulation

- Read Environmental Management, book 1, chapter 10, pages 137-148: Economic Policy Instruments – Taxes and Fees

- Study the policies and roles of World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

Advanced level (deepening)

- Examine critically the concept of Green Growth, e.g. see:

Green Business

Green Growth in Asia and the Pacific - Learn about sustainability reporting at Global Reporting

References

Klemmensen, B., Pedersen, S., Dirckinck-Holmfeld, K. R., Marklund, A. and L. Rydén. 2007. Environmental Policy: Legal and Economic Instruments. Book 1 in a series on Environmental Management. Baltic University Press. Uppsala.

Zyclicz, T. (ed.). 1997. Ecological Economics – Markets, prices and budgets in a sustainable society. A Sustainable Baltic Region. Session 8. Baltic University Press. Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

11a.

The processes of individual change

Sustainable development will not be reached unless we change, as individuals, organizations, authorities, and societies. In this session we will study and attempt to describe the processes that lead to change and how each one of us as an individual can contribute to change.

On the individual level, change is dependent on our understanding, of attitudes and behaviour. Theories of individual change have been advanced in the fields of psychology and education, in areas of culture, of medicine and health, and in environmental science. Recent research suggests that individual behaviour change is not foremost a question of knowledge and rational choice. It rather depends much on social interactions, lifestyles, norms and values, as well as on support from tailored information, policies, and technologies. In addition, individuals are different. Some people are more likely to change than others, perceive risks differently, and possibilities to change vary for a person during his/her lifetime.

The natural tendency of most individuals is to preserve what they have rather than trying something new, even if it is expected to be better. This resistance to change is explained by status quo is perceived as having a higher value, change itself being uncertain, and that change requires an effort. As a result, most people are habitual. Resistance to change may take many forms, including active or passive, overt or covert, individual or organized, aggressive or timid. As change does not happen, the consequence of not changing is postponed to the future. Sometimes this is serious, as in the economic crisis, but it is equally serious for many environmental issues, including the ongoing global warming.

Change or lack of change is also connected to the perception of risk. This is mostly very irrational and depends on other factors than on carefully calculated data. Risk may be ignored, e.g. when it comes to car driving or bad habits for health. Risks may also be exaggerated. For example, air travel is perceived as dangerous by many, although it is far safer than the car trip to the airport. Risk of climate change has been calculated by the IPCC as very high, about 50% risk of more than 2 degrees global warming (and probably more in most recent estimations). This risk is seldom well understood.

In some situations, a risk may, however, be understood as very real. Thus, when patients who had survived a heart attack were told by their doctors that they had to change behaviour to avoid an almost certain imminent death, there were two kinds of reactions to threat. Some faced the danger, learned much about heart illness and changed behaviour. Another group was unwilling to change, disregarded and played down the danger and did not change. Today, these patients are offered a program to learn a new behaviour. A similar spilt between two types have been seen when it comes to the threat of nuclear war or for that matter climate change: Some face the danger, learn about it and change, but many rather avoid the topic and play down the risks.

Individuals thus differ between themselves. Personality features as well as the way a person perceives his/her situation and the world is important for his/her possibilities to change. People can be categorized in many ways. Michael Thompson, in his cultural theory of risks, differentiates between three categories. The individualists rely on human ingenuity and maintain that there are enough natural resources for all of us. He/She assumes that technological progress will take care of environmental problems. Egalitarians on the contrary assume that Nature is already under severe stress and that environmentally less damaging lifestyles are urgently needed. Hierarchizes are between the two, as they assume that a certain risk to Nature can be accepted if we pursue broader social goals. It is clear that today the world is run by individualists promoting economic growth rather than nature protection.

Which are then the factors, the incentives, which lead to behaviour change? Behaviour change has been studied as part of health research. In this field it is clear that information about a behaviour (smoking, drinking etc) being damaging does not automatically lead to change. Information alone rather seems to have very little effect, even if health is an important value. This is also true for behaviour related to the environment. Values and information are thus by themselves limited as incentives to behaviour change. Nor is regulation by itself an important incentive. For example, the law on obligatory safety belts in cars did not have an immediate effect. Change is more readily accepted if it is voluntary, and it is then also more long-lasting.

If knowledge does not lead to behaviour change, what then may initiate a change process? New information does lead to change of behaviour if the consequences of the information are immediate, for example “do not feed the wolf, he will bite you”. But information on environmental matters is seldom related to immediate consequences. The consequences are typically far away, often both in time and space. One may instead assume that information may lead to increased awareness of an issue, which is followed by behaviour change. But at least in the field of environment, research suggests that it is rather the other way around. It is new behaviour, which leads to new knowledge, which, if deepened, is followed by a change in attitude.

If knowledge does not lead to behaviour change, what then may initiate a change process? New information does lead to change of behaviour if the consequences of the information are immediate, for example “do not feed the wolf, he will bite you”. But information on environmental matters is seldom related to immediate consequences. The consequences are typically far away, often both in time and space. One may instead assume that information may lead to increased awareness of an issue, which is followed by behaviour change. But at least in the field of environment, research suggests that it is rather the other way around. It is new behaviour, which leads to new knowledge, which, if deepened, is followed by a change in attitude.

Thus, the typical change process starts in the practical situation. The concrete situation, the antecedents, is important for behavioural change. An antecedent is what is there before the effort to induce a change. The practical conditions should be such that the new behaviour is easily accessible. It is easier to buy eco-labelled products if you see them on the shelf, and it is easier to stop smoking if there are no cigarettes around. The environmentally adverse behaviour should be difficult to carry out, while the good behaviour should be easy.

Also, important are the consequences of a behaviour change. Since the effect on the environment itself is seldom immediate, one needs to construct “artificial” consequences to promote behavioural changes. These have mostly been economic, e.g. decreasing energy costs when saving energy, or smaller fees for waste management if the waste is sorted. Economic incentives are extremely important. It is crucial that environmentally good behaviours should be less expensive than environmentally bad. This is mostly done by taxations. Thus, a high tax on carbon dioxide emissions is a very efficient way to achieve a change to non-fossil fuels.

A British 2008 governmental report on policy frameworks for promoting environmentally more sustainable patterns of consumption and production concluded that a most important condition is proper social norms. A first condition for municipalities was structures needed for proper environmental management (the antecedents!). E.g. provision of kerbside recycling will raise recycling rates without any underlying shift in culture or attitudes. But the second most important determinant of whether someone recycles is whether his/her neighbour does – which can be regarded as a proxy for the extent to which the behaviour has become a social norm.

A British 2008 governmental report on policy frameworks for promoting environmentally more sustainable patterns of consumption and production concluded that a most important condition is proper social norms. A first condition for municipalities was structures needed for proper environmental management (the antecedents!). E.g. provision of kerbside recycling will raise recycling rates without any underlying shift in culture or attitudes. But the second most important determinant of whether someone recycles is whether his/her neighbour does – which can be regarded as a proxy for the extent to which the behaviour has become a social norm.

In summary, to achieve change in behaviour one first needs to arrange the practical situation, so the new behaviour is easy to carry out. Secondly the new behaviour should at best be profitable, that is economically better than the old one, e.g. by new charges, taxes, or subsidies. If enough members of the society adopt the new behaviour, it becomes a social norm and is then further accepted and strengthened. This may lead to knowledge on the reason for the new behaviour and a new awareness in society.

Materials for session 11a

Basic level

- Study behaviour change theories in the Environmental Science, chapter 21: Behaviour and the Environment, especially pp 651–658.

- Read pages 47–48: Individualists, Egalitarians, Hierarchists – Three Ways to Perceive the World in Environmental Management, book 3, chapter 2: Resource Flow and Product Design.

Medium level (widening)

- Study pages 7–17 in Achieving Culture Change: A Policy Framework (UK government report, 2008).

Advanced level (deepening)

- Study Behaviour Change – A Summary of Four Major Theories as used in HIV/AIDS prevention.

- A longer report of behaviour change is the Government Social Research (GSR) report Behaviour Change Knowledge Review Reference Report: An overview of behaviour change models and their uses by Andrew Darnton, Centre for Sustainable Development, University of Westminster 2008. Read especially “2.3 The role of information and the value action gap” pp 10–15.

References

Darnton, A. 2008. Reference Report: An overview of behaviour change models and their uses. Centre for Sustainable Development, University of Westminster. UK:

Family Health International (FHI). 2002. Behavior Change – A Summary of Four Major Theories. Arlington, VA. USA.

Rydén, L., Migula, P. and M. Andersson (eds). 2003. Environmental Science – understanding, protecting and managing the environment in the Baltic Sea region. Baltic University Press. Uppsala.

Zbicinski, I., Stavenuiter, J., Kozlowska. B. and H.P.M. van de Coervering. 2006. Product Design and Life Cycle Assessment. Book 3 in a series in Environmental Management. Baltic University Press. Uppsala.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

11b.

Social change and transitions of societies

Sustainable development requires social change, even a transition to a new society, a grand vision. What do we know about social change? How does it occur, which are the processes, which contribute to or hinder social change? This is the topic of this sub session.

It is clear that large social transformations occur repeatedly in history. We have the large civilization changes – from an agricultural society to an industrial society and then to a service oriented society. These transitions occurred as different sectors, which provided resources to society, changed fundamentally. In the agricultural society, some 85% were working in “food-producing” agricultural (primary) sector and lived on the countryside. In the industrial society, some 70% were working in “products-producing” manufacturing (secondary) sector and living in cities. This figure has in the service society decreased to 11-12%, while 70% work in the “service-providing” (tertiary) sector, and urbanization increased to some 85% or more. This development has been caused by technological and organizational developments, such as large-scale production, new machinery, and automation, but equally important is access to new resources, not the least fossil energy. The transitions are also characterized by a steadily increased use of resources.

It is clear that large social transformations occur repeatedly in history. We have the large civilization changes – from an agricultural society to an industrial society and then to a service oriented society. These transitions occurred as different sectors, which provided resources to society, changed fundamentally. In the agricultural society, some 85% were working in “food-producing” agricultural (primary) sector and lived on the countryside. In the industrial society, some 70% were working in “products-producing” manufacturing (secondary) sector and living in cities. This figure has in the service society decreased to 11-12%, while 70% work in the “service-providing” (tertiary) sector, and urbanization increased to some 85% or more. This development has been caused by technological and organizational developments, such as large-scale production, new machinery, and automation, but equally important is access to new resources, not the least fossil energy. The transitions are also characterized by a steadily increased use of resources.

But social change also refers, equally important, to a change in the social order or organization of society. Changes of social order include the transition from authoritarian to democratic government, from feudalism to capitalism and market economy, and the development of the welfare state; the rise of the civil rights movement and the acceptance of human rights; the development of the environmental protection movements; and not the least globalization, and large-scale use of information technologies. All these changes may be included in modernization, the processes that take a society from traditional to a modern. Modernization eventually seems to replace the key position of the family in society with the individual, and reduces the role of the church and see a growth of a more secular culture.

Finally, social change may also refer to political changes. These include de-colonisation, increased global cooperation and trade, less concern with military power, to economic growth as a primary political goal. A dramatic, unexpected and rapid political change was the end of the Cold War, when Central and Eastern European states changed political system as they left the communist block to become “states in transition” towards democracy and market economy. First a majority of inhabitants were all positive to the changes, but very soon sentiments changed and many missed the old system. It has taken close to a generation to adapt to the new social order, an adaptation still going on.

This social change may be a case of future shock, a change dangerous to a society and to sensitive individuals. The concept was introduced by Alvin Toffler in 1970 for a situation when persons perceive “too much change in too short a period of time”. He believed that the accelerated rate of technological and social change and information overload could leave people disconnected and suffering from “shattering stress and disorientation”. A similar concept is culture shock. It is the alienation and anger, which may occur when a person is transferred to a new culture. Culture shock is most often used in connection with migration.

The question of how social change is brought about has since eternity occupied thinking, as it has been on the agenda in all societies. Is it a sudden change, a revolution, or a slow change, an evolution? Is it by struggle and fight, or is it by political activism and persuasion? There are many examples of how one process transformed into the other. In an authoritarian regime, civil society has more difficulties to influence these changes; in a democratic society, the decision to change should hopefully be the result of a democratic process.

In a bottom up process, recruitment of members of society to the new cause is the key step to take. How many are needed to achieve a change? One study proposes that when just 5% of a society accepts a new idea, it becomes “embedded”, and when 20% adopt the idea; it is “unstoppable.” The study also shows that it normally requires 50% of the population to be “aware” of the idea in order to reach the 5% who will adopt it. Certainly, these figures are different for different ideas and societies, but they give us an idea of how social change may work. In a more authoritarian system, distribution of power is the crucial factor deciding on who could initiate and implement change.

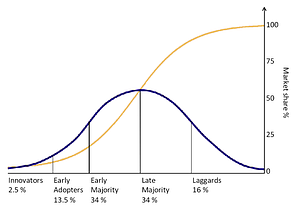

Diffusion of innovations was more rigorously studied by Everett Rogers, a professor of sociology. In 1962, he published his well-known theory of how innovations are adopted in society, among individuals and organization. Individuals progress through five stages: knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation. The main elements that influence the spread of a new idea are the innovation itself, communication channels, time, and the social system. It progresses through several actors known as innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards.

Diffusion of innovations was more rigorously studied by Everett Rogers, a professor of sociology. In 1962, he published his well-known theory of how innovations are adopted in society, among individuals and organization. Individuals progress through five stages: knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation. The main elements that influence the spread of a new idea are the innovation itself, communication channels, time, and the social system. It progresses through several actors known as innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards.

Which are the actors in social change processes? Social movements play a vital role as discontent members of society push for a change. There are also resistance to change, especially when those with vested interest understand that they will suffer in case the proposed change is brought about. We see this clearly in the climate change discussion, as typically those who will lose when the old system based on fossil fuels is replaced will protest or typically deny that there is a problem with global warming.

The transition to a sustainable society at present seems to be far away in time. Instead of adapting to the existing limits to growth and resource flows which the environment can cope with, policies in the world are promoting economic growth, as an overarching goal. John McNeill suggests (See Chapter 1a) that it would be more reasonable to focus on energy and demography than growth. The economist Nicholas Stern (See Chapter 2b) concluded that it is far better to invest about 1% of GDP in mitigation of climate change now, instead of suffering much worse costs in 20 or so years. But the world is postponing changes. They are perceived as costly and less pleasant, even if some may accept them as unavoidable in the longer terms. In this way, the transition to a more sustainable society is similar to the economic crisis. Loans are taken to keep lifestyle unchanged. In the meantime, consequences become more serious, as the change is postponed.

Materials for session 11b

Basic level

- Why does a society develop the way it does? By Gene Shackman, Ya-Lin Liu and George (Xun) Wang. A Review of Theory About Social, Political, Economic Change of The Global Social Change Research Project. Study the beginning of the website, The Global Social Change Research Project.

- Study The Process of Social Change by Len and Libby Traubman.

- Diffusion of Innovations by Everett Rogers and the idea of tipping points where a new idea catches fire. Does it exist? A review by Greg Orr, Stanford University

Medium level (widening)

- Study Achieving Culture Change: A Policy Framework (UK government report, 2008) 2. The concept of culture change, pp 23-38.

- Read A Three-fold Theory of Social Change and Implications for Practice, Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation by Doug Reeler, of the Community Development Resource Association, 2007

Advanced level (deepening)

- Why does a society develop the way it does? By Gene Shackman, Ya-Lin Liu and George (Xun) Wang. A Review of Theory About Social, Political, Economic Change of The Global Social Change Research Project.

- Study the role of NGOs in The rise and role of NGOs in sustainable development from International Institute for Sustainable Development, IISD

References

Knott, D., Muers, S. and S. Aldridge. 2008. Achieving Culture Change: A Policy Framework. A discussion paper by the Strategy Unit. Admiralty Arch, The Mall, London SW1A 2WH.

Reeler, D. 2007. A Three-fold Theory of Social Change and Implications for Practice, Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation. Community Development Resource Association.

BUP Sustainable Development Course

Sida 11 av 15